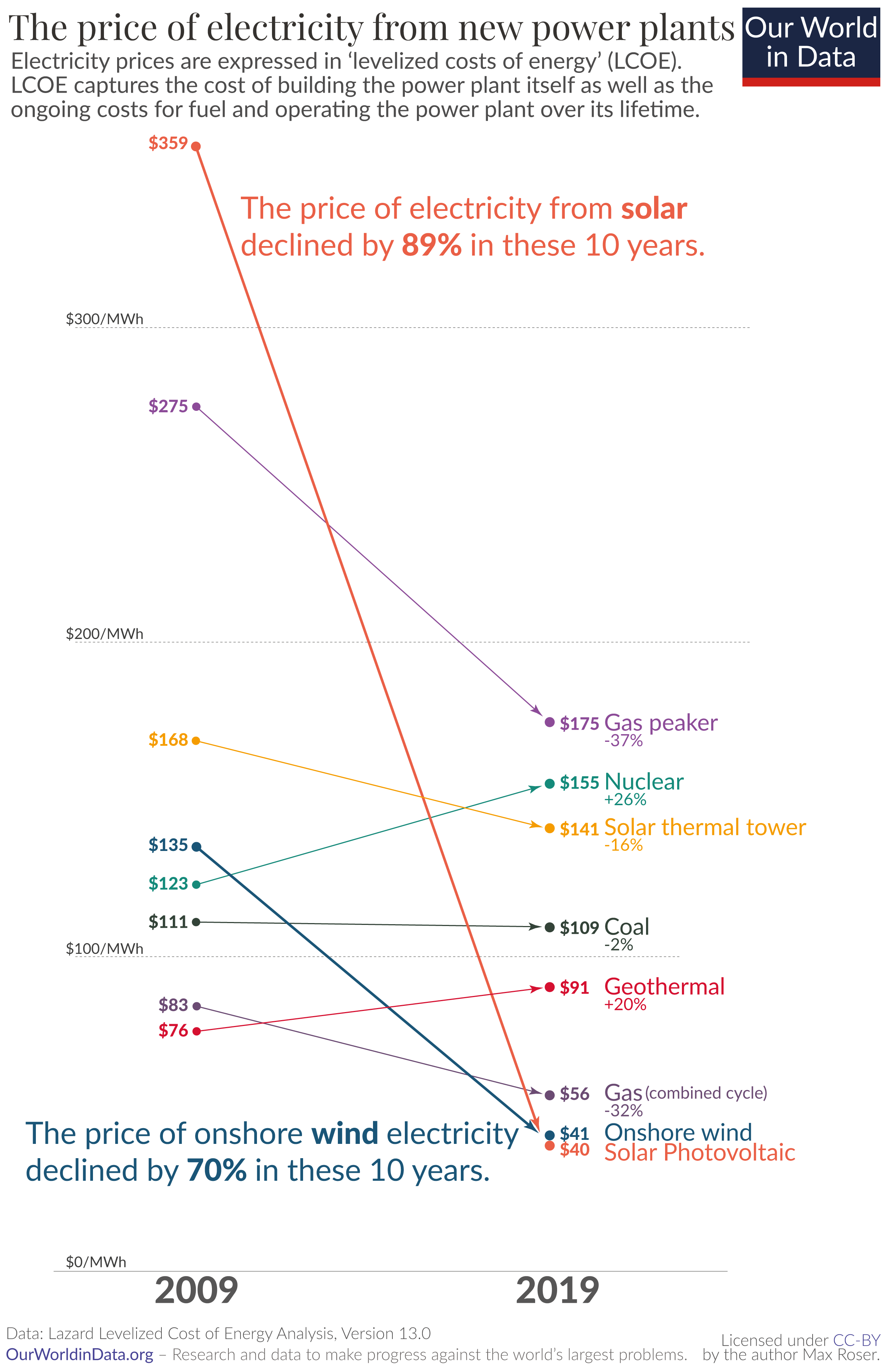

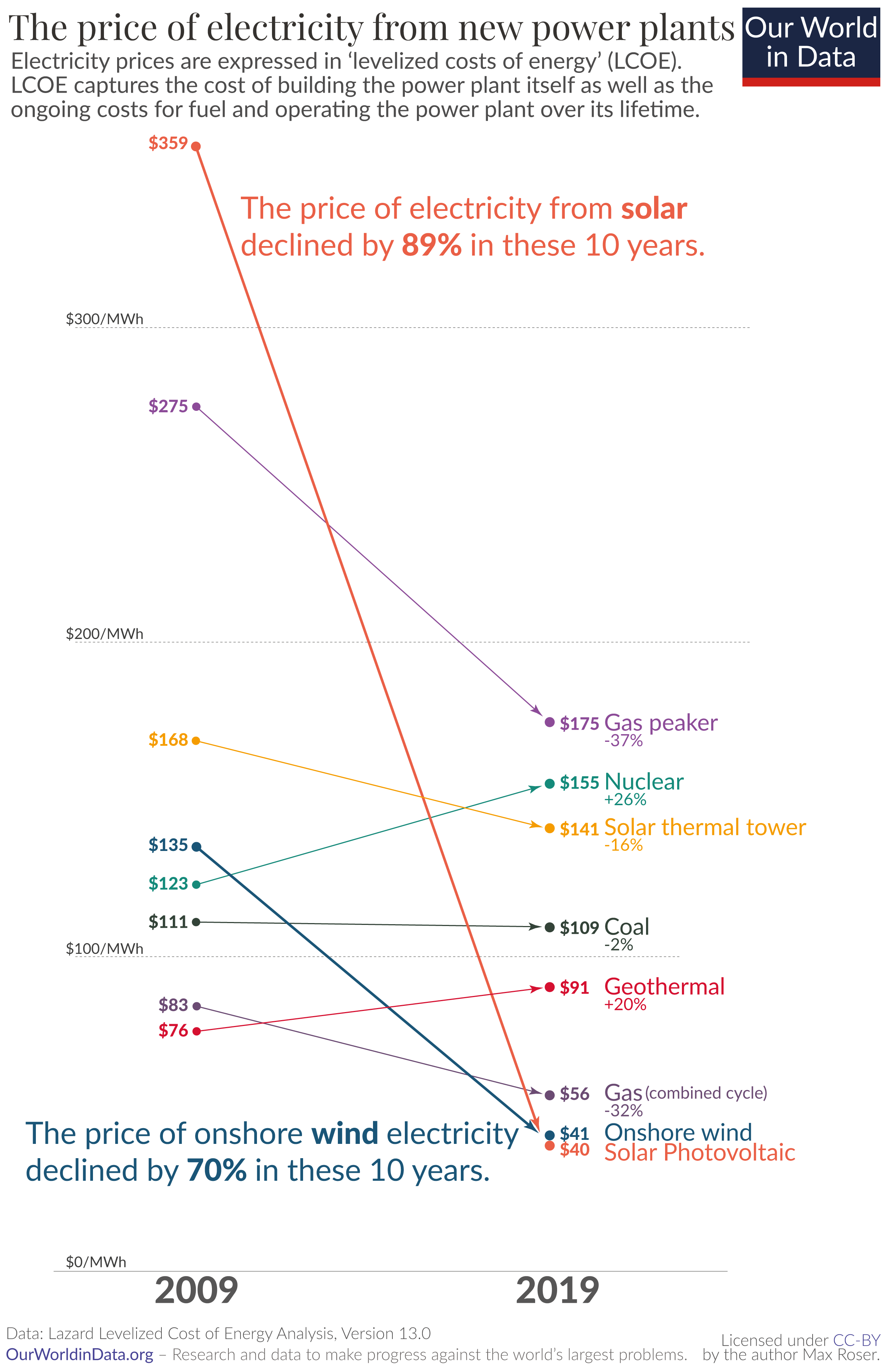

Electricity prices from renewables decline noticeably over the last 10 years

Electricity prices from renewables decline noticeably over the last 10 years

Slobodian argues that one of the neoliberal objections to socialism was that because we cannot see or predict the economy we cannot govern it or reform it democratically. The ‘economy’ as such does not exist. Partly because the term oeconomy comes from Greek and means the governance of a household, not the governance of a polis or a wider sphere, which cannot, according to neoliberals, be governed in any useful way for the populace.

Hayek, for example, “says more than once in his writings that one of the great fallacies of the twentieth century is the belief that there is something called the economy, that can somehow be seen and controlled and managed. And he could say that because the invention of the economy was mostly a social democratic, Keynesian project” aimed at maintaining full employment and survivable wages. Inventing the economy “was a project of governing and collectivizing risk.” [1]

As Hayek says in his Nobel speech, “it is ‘the pretense of knowledge,’ to think that you can actually have any kind of oversight over the economy as such.” [1]

As this economy does not exist (hence Hayeks use of the term ‘catallaxy‘ for what people would normally call the economy) we can only use very precise rules to protect the market and submit to it: “we must give ourselves over to the forces of the market, or the whole thing will stop working” [2].

The only neoliberal liberty is submission to the limited options the market allows. “The normative ideal for the individual is a kind of total subjection to the forces of competition. We gain our freedom insofar as we subject ourselves to that.” [1]

Neoliberalism needs a market police to prevent people from “kept trying to make the earth a more equal and just place.” This interest people might have in not being ripped off, is a special interest in neoliberal terms, whereas corporations do not have such special interests – their interests are just the market in action. [2]

The big public idea promoted by neoliberalism is that if the ‘catallaxy,’ or what people would normally call the economy, is defended, then all will work out well or at least as well as we can ever expect.

A more recent way of dealing with this problem, is to realise that the ‘catallaxy’ is a complex system and it is embedded in other complex systems, which are important for its functioning and survival.

Crucially, it is helpful not to subscribe to a dogmatic optimism about complex systems. Complex systems, no matter how adaptive, will not always seek a balance, harmony and efficiency which are beneficial to humans; they may require some mild corrections or interventions to achieve anything resembling what we might consider beneficial for most people, never mind all people.

This presents a problem as complex systems cannot be governed rigorously or in a guaranteed manner, neither can specific events be predicted.

We can, however, seek patterns of complex behaviour, and we can make general trend like predictions, and adjust things accordingly and carefully, getting rid of what has not been working.

It may not have been possible to predict Trump or his specific actions and failures, but we can predict that if democratic control over the economy is completely surrendered we will likely head for plutocracy, as massive wealth is where the power is. Plutocracy will likely head towards autocracy, and autocracy can look like fascism, or arbitrary rule. Consequently, we need to be aware of this possibility, and do our best to prevent it in advance, should we wish to maintain freedom.

We can predict that neoliberal ‘free markets’, will lead to a decline in the share of the wealth, generated by society, going to ordinary people defeated by the market. This will almost certainly reinforce the power differentials, and likely lead to the problems of ordinary people being dismissed from consideration. Again we need to undermine this possibility, possibly by redistribution of wealth and inheritance.

We can predict that market crashes will happen more frequently, and that big business will get bailed out by the tax payers (as the point of agitating for what are called ‘free markets’ is to protect big business) and that small people will suffer. Again we can shift our focus from just protecting the “big end of town” and make sure we attend to people in general.

We could have predicted that neoliberals would try and force people to catch a pandemic in the hope of keeping the economy going, and that they will agitate for massive taxpayer support for industries which were already failing before the pandemic hit. Mass death, and long-term disease generated incapacity and injury in people, will not help the economy recover in a way which benefits everyone in the long term. The neoliberal method is not the best for dealing with all problems. The health of the economy, can depend upon the health of the social system and people in general. Free markets cannot be isolated from everyone.

We can predict that if we do not protect and regenerate environments and ecologies, that the survival system as a whole will crash and that large numbers of people will be displaced and die – we can also predict that neoliberals, devoted to protecting existing big businesses, will object to protecting environments as it is a cost to profit, and they will spend a lot of money to persuade people they are correct. However, we do not have to accept massive environmental destruction as a part of the capitalism we need to gain a working economy. We can probably solve this problem by regulating emissions and destruction for all companies equally, and making it easier for local people to take destructive and polluting companies to court. This way, people get to participate in deciding what kind of environment they have to live in. Capitalists get to solve the problem of keeping ecologies functional, by making destruction and pollution a cost, or potential cost, to them.

It may be impossible to completely regulate markets and ecologies, but that does not mean that we have to let the bad results completely triumph. We experiment, and try and see what works, and consider the possibility of stopping doing whatever delivers more harmful results.

There is no reason we cannot have freer markets than we have now, with democratic input into preventing harmful, monopolistic, ‘crony’ and authoritarian corporate behaviour as it evolves, and with a dedication for protecting life on Earth.

Neoliberals appear to want to stop that from happening, as it challenges corporate liberty to do whatever corporations want at the expense of the populace.

Liberty is necessarily a balancing act.

I have just encountered the writings of Quinn Slobodian. He has an interesting take on the role of the State in Neoliberalism, and Austrian Economics. It is worth looking at, but I have not yet read his major book The Globalists. His arguments make it clearer that Neoliberals and Austrian Economists are not Libertarians, or anarchist at all, despite the support they receive from Libertarians. Neoliberals primarily want protection of markets, and market organisation, from States, but have no objection to States in principle, as long as those States defend markets and market power – especially against the people.

Neoliberals attempt to “to insulate the markets against sovereign states, political change, and turbulent democratic demands for greater equality and social justice.” [1] For them, the State exists to protect capitalism, its extracted property and the world economy as it is, not to open the economy to ordinary people on equal terms. Neoliberalism was “less a doctrine of economics than a doctrine of ordering—of creating the institutions that provide for the reproduction of the totality [of the system].” [2]

Consequently, neoliberalism is a form of regulation rather than a form of anarchism. It probably developed as a preventative response to socialist movements, and the fact that their favoured fascism did not provide quite the defense of property that they had otherwise expected.

Mises argued that communists were murderous and the fascists reacted reluctantly in kind, but they, unlike the Russians would be unable to get rid of thousands of years of civilisation. Mises wrote in 1927 that:

Because of this difference, Fascism will never succeed as completely as Russian Bolshevism in freeing itself from the power of liberal ideas…. Fascism, in comparison with Bolshevism and Sovietism, [i]s at least the lesser evil.

Mises Liberalism, Online Library of Liberty: p: 49.

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aimed at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has for the moment saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history. But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error.

[3], & Mises Liberalism. Online Library of Liberty: p: 51. emphasis added.

This was not uncommon at the time. Slobodian remarks that Carl Schmitt “saw the need for what was effectively a fascist state as a way to prevent the rise of totalitarianism.” [4]

[I]n the late 1930s, Wilhelm Röpke, another leading neoliberal, would unabashedly declare that his desire for a strong state made him more “fascist” than many of his readers understood. We should not take this as a light-hearted quip.

[4]

In other words Fascism, and the autocratic State, was useful to maintain capitalism and its civilisation for a while. There seems little objection to the idea of an ‘intellectual’ fascist State as such, and of course, Mises could not understand where German fascism was to go. However, he fled the Nazis after the occupation of Austria.

Later on (1951) Neoliberals such as Mises and Hayek were to conflate Fascism and Nazism with socialism and Bolshevism, which ignores who sponsored them and why, and indicates a degree of hard and misleading binarism in their thinking. Socialist democracy in the UK and Australia between 1950 and the early seventies, and Scandinavian socialism is, according to them, the same as Nazism, Stalinist Communism and so on. If it is not the capitalism they support, it must be socialist, and must be evil. There is no ability to see degrees here, everything ‘bad’ is lumped together, as politically useful to support the idea that free markets lead to liberty, rather than to plutocracy and potential fascism.

We may also note the hostility of neoliberals to any effective idea of equality. Equality, in their view always demands an interventionist State, and therefore an authoritarian State of the wrong kind. Again the hard binarism is brought into play. They take a position we all know to be correct, namely that some people are more talented, dancers, musicians, painters, mathematicians, preachers, basketball players, swimmers etc, (and that some of these people work really hard to make themselves better), to say that one unlimited distinction in power and wealth between people based on the talents of business or inheritance is equally banal, harmless and even pleasurable.

Truly massive power and opportunity differences produced by the corporate market are to be defended at all costs, with the implication is that if you don’t succeed, you are inferior.

Neoliberals want to suppress the power of democratic peoples to challenge corporate capitalism and its wealth based power – and to prevent any kind of relative equality which might allow people to challenge corporate power. Hence the conflation of socialism, fascism and democracy, and the initial wary support of fascism which was common amongst the conservative and pro-capitalist Right at that time for similar reasons.

The basic neoliberal position is that governments by attempting to control or interfere in the workings of the market generate inefficiency and autocracy – but it seems they refuse to consider the effect of corporations interfering in the working of the markets – or make it beneficial as with their denial of the market powers of private monopolies.

Therefore regulatory movements, and labour movements aiming at improvements for workers, or colonised people, must be crushed. Neoliberals had no objection to regulating protest against their favoured economic set up. Mises was, for example hostile to labour movements, and supported their suppression.

This led to some neoliberals supporting apartheid [3]. We are also left with Murray Rothbard’s lament against Martin Luther King:

mass invasion of private restaurants, or mass blocking of street entrances is, in the deepest sense, also violence. But, in the generally statist atmosphere of our age, violence against property is not considered “violence;” this label goes only to the more obvious violence against persons

Essentially, hurting property is as bad as harming people.

“Any lingering idea that neoliberals are anti-state will be dispelled because you can see that, in their own writings, the whole project of neoliberalism is about redesigning the state, especially in questions of law.” [4]

“Even a superficial reading of the primary texts of neoliberals makes this clear. Milton Friedman’s Economic Bill of Rights, James M. Buchanan’s fiscal constitutionalism, F. A. Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty, Gottfried Haberler’s proposals for GATT, Ernst-Joachim Mestmäcker on European competition law, William Landes and Richard Posner on intellectual property rights—the list goes on.” [5]

To some extent their way forward was through setting up international modes of regulation that were, explicitly non democratic, and not responsive to the people anywhere, such as the WTO.

This is not to say, that post the internationalist age, neoliberals are not comfortable with promoting nationalism and even tariffs if it helps support corporate power, or is seen as a tactic in compelling ‘free trade’. [7]

There is no “one-to-one transposition of blueprints from the pages of Hayek or Haberler or whomever to reality in some unmediated or direct way.” Ideas work through “uptake by domestic actors, who find certain of their own interests fulfilled by adopting neoliberal policies.” [4]

“The only reason why empire works is that it finds willing compradors and domestic elites who will do the work of empire for the metropole for the most part.” [4]

And this may have unintended effects (along with complexities of markets). For example:

Intellectual property rights become part of the WTO not because Friedman or Posner wanted them to be there, but because pharmaceutical companies, software companies, apparel companies, entertainment companies wanted them to be there and were very good at lobbying.

[4]

In other words, putting defense of the corporate market first, opens up further opportunities for important players to twist the market into favouring them, and diminishing the rights of ordinary people – in this case to use their own culture. In other cases we may note neoliberal attempt to defeat people’s right to drink non-poisoned water, and breath non-polluted air, and eat safe food.

Defending corporate liberty to pollute, set up monopolies, set up their own laws and police, or pay for politicians and political propaganda, may well set up the circumstances in which other people’s liberty is severely curtailed. Their liberty may not equal yours.

This loss of public liberty might count as an unintended consequence of neoliberal politics and theory intended to defend liberty but, then again, it might not.

This is another go at formulating a list of basic systems which need to be considered for eco-social analysis. For earlier versions see here, here and here.

As a guide to the factors involved in eco-social relations we can point to a number of different, but interacting systems. This list is not claiming to be complete, but it can be used as a set of reminders when we try to make analyses of our contemporary situation, and we may be able to make some general statements about how they interact. The order of relative importance of these systems is a matter for investigation, and the order of their presentation, in this blog post, is not a claim about their relative importance.

The seven main systems, discussed here, are

All these systems are complex systems, and it is generally impossible to predict their specific course. They are also prone to rapid change, gradual instability, and the ‘seeking’ of equilibrium.

The political system, includes:

Politics can affect all the other human systems. What activities (extraction, energy use, organisation etc.) are encouraged or discouraged, the kinds of regulation that apply, what counts as pollution or risk, what information is easily available, and who is to be trusted, and so on.

Political systems can forcibly ignore pollution or the consequences of energy production, economic extraction, the wage system, and so on, effectively rendering them part of a general unconscious, which eventually ‘bites back’.

Most of the dominant economic systems currently in action can be described loosely as ‘capitalist’. The economic system involves modes of appropriation, extraction, property, commodification, exchange, circulation of ‘products’, technological systems, energy use, as well as accumulation of social power and wealth and so on. Most of which depend upon the State for their existence and reinforcement, although they may also challenge organisation and politics within the State. There is no inherent stability in current economic systems.

In many sociological theories the patterns of economic organisation and behaviour are known as the ‘infrastructure’ and are held to be determinate of most other social behaviours, primarily because the economic system seems the most obvious determinate of what people have to do in order to survive.

This organisation may have apparently unintended consequences, such as producing periodic crashes, or destroying the ecological base of the economy, and therefore threatening that organisation. They also may have quite expectable consequences, which are downplayed. In capitalism, political and economic patternings tend to be describable as ‘plutocratic’; as wealth allows the purchase of all other forms of power. However, different factions in the State can ally with different or competing factions in the economic system. For example, different government departments or political factions can support different types of energy: fossil fuels, renewables, or nuclear. The political system legitimates and enforces, allowable modes of extraction, property and pollution, and regulates economic behaviour among different social groups. Economics always involves political as well as economic struggle; politics is part of ‘the market’. ‘Crony Capitalism’ is normal capitalism.

The Extraction system is part of the economic system, but it might be useful to separate it out from the economic system because extraction is one of the prime ways in which economies interact with ecologies and because different kinds of economies can use similar extraction systems. Extraction not only involves extraction of what gets defined as ‘resources’ (minerals, naturally occurring substances such as oil, coal or timber, and so on) but also the ways that human food gets extracted for consumption, via agriculture, gathering, hunting, industrial fishing, and so on. Ecologies are not passive, and they respond to human or other actions in ways which are often unpredictable in specific, but still disruptive. Ecologies seem to need attention, for survival to be possible in the long term.

Extraction in capitalist and developmentalist societies, often seems harmful to the functioning of ecologies, perhaps because of the need for continual growth, and thus a need for increasing extraction. Clearly, not all forms of extraction need to be destructive of the ecologies and geographies they depend upon. Extraction systems can allow the ecologies to repair after extraction, or attempt to rehabilitate the land. However, repair of ecologies can be considered an expense leading to reduction of profit, and hence is not attractive in a profit emphasising system.

As such, we can distinguish recoverable extraction, in which the ecologies and economies repair the damage from extraction, from irrecoverable extraction in which the ecologies and economies do not repair the damage from extraction within a useful time frame.

The Global Footprint network, suggests that:

Today humanity uses the equivalent of 1.6 Earths to provide the resources we use and absorb our waste. This means it now takes the Earth one year and eight months to regenerate what we use in a year.

Global Footprint network. Ecological Footprint

If this is correct, then the current extraction and pollution systems are generally irrecoverable, and deleterious for human and planetary survival. Investigating the differences between harmful and less harmful modes of extraction may well produce useful insights.

Economies are not the only possible harmful extractive systems – cosmologies can also require irrecoverable extractive behaviour to build temples, or to show the ‘other-worldly’ specialness of humans, and so on.

All life and its resulting ecologies involve transformation of energy. These transformations stretch from transformation of sunlight by plants, the digestion of plants, to thermal gradients in the deep sea, to atomic power. Eco-systems require a system of energy release, energy generation and energy transformation.

Transformation of energy, together with effective ecological functioning, is necessary for any human actions to occur. The human energy system powers all other human systems. Because food is necessary for human labour, cultivation of food can be considered to be part of the energy system. The energy system and its ‘infrastructure’, could seem to be as important as the economic infrastructure.

The human energy system is organised, at least in part, by the political and economic systems, and by the environmental systems available. The environmental system includes possible energy sources from plant material, animal strength and docility, fossil fuels, sunlight, wind and moving water. Human labour, and its organisation, is (and has been) part of the energy system, and while not yet, if ever, superseded completely, can be supplemented and possibly overpowered by technological sources of energy. Coal and oil power, for example, provide masses amounts more directed energy than can human labour, and this ability is important to understanding the patterning and possibilities of the economic and extraction system, and its relationship to colonial/imperial history. Modern military expansion and colonialism, largely depends on this ability to apply large amounts of energy to weaponry, movement and organisation.

Important parts of the energy system include the amounts of energy generally available for use, and the capacity for energy to be directed and applied. Non-directable energy is often wasted energy (entropy), and usually unavailable for constructive use.

Another vital point is that human production of, or using of, energy takes energy. No energy is entirely free.

The availability of energy is influenced by the Energy Return on Energy Input (EREI) or ‘Energy Return on Energy Investment’. The larger amount of units of energy applied to gain a unit of humanly directable energy output, the less excess energy is available.

Fossil fuels have historically had a very high EREI, but it is possible that this is declining otherwise nobody would be tempted by fracking, coal seam gas, tar sands, or deep sea drilling. All of which require large amounts of energy to begin with, have very high risks of extractive destruction, and fairly low profit margins when compared to the dangers.

Renewables and storage currently have a high energy cost to manufacture (and possibly a high extractive cost as well) but for most renewables, after they are installed, the EREI changes, as very little labour, or energy expenditure, is required to gain an energy output – it is more or less free – whereas fossil fuel energy generation requires continual energy use to find and process new fossil fuels and keep the power stations turning, and produce continual pollution from burning.

Social power and economics may affect the ways that energy is distributed, what uses are considered legitimate and so on. However, the energy system also influences what can be done in other systems, and in the costs (social, aesthetic, ecological or monetary) which influence choices about the constituents of energy systems The system’s pollution products, which may be significant factors in producing climate and ecological change, may eventually limit what can be done.

As the energy system determines what energy is available for use, it is not an unreasonable assumption that social power and organisation will be partly built around the energy system, and that changes in energy systems will change energy availability, what can be done or who can do it, and thus threaten established social orders. Threats to established orders will be resisted. If an energy transition does go ahead, it is likely that the established orders will try and preserve the patterns, of organisation, wealth and social power which have grown up under the old system.

One important question is ‘how do we transform the energy system without continuing a damaging extraction and pollution system?’

Transformation of materials through energy use, or through energy production, produces ‘waste’. The simplest human society imaginable (and this is an overt simplification), turns edible material into energy and human excreta, which in this case can usually be processed by the ecology – although, even then, dumping excreta into rivers may not help those downstream.

Understanding the Waste, Pollution and Dispersal systems is also vital to understanding possible energy and economic transformations.

In this book we will define ‘Waste‘ as material which can be re-processed, or recycled, by the economy or eco-system, and ‘Pollution‘ as material which is not re-processable within an arbitrary useful time frame, say over hundreds of years or more. ‘Dispersal’ occurs when some essential material is dispersed into the system, and becomes largely unavailable for reuse without ‘uneconomic’ expenditures of finance or energy – as occurs with helium and phosphorus.

When too much waste for the systems to re-process is emitted, then waste becomes pollution. This is what has happened with CO2. CO2 is normally harmless, even required for the system to work, but too much CO2 changes the ways eco and climate systems work. CO2 has also been dispersed into the atmosphere which makes CO2 extraction, which is stated to be essential by the IPCC and IEA for climate stability, difficult and costly in terms of energy expenditure.

These concepts, along with ‘extraction’, directly import the ecosystem into the economy, while pointing out that what counts as allowable waste, pollution or dispersal can change, economically, politically, scientifically and ‘practically’.

Waste, pollution and dispersal from the energy system and from modes of extraction, enter into the political system because that system decides and regulates what can be emitted, and where, and who is too valuable to be poisoned by the pollution. The political makes the laws allowing, diminishing or preventing, pollution. Often localisable pollution is dumped in ‘wasted’ zones or on poorer, less noticeable and less powerful people.

Energy and extraction may not the only significant sources of pollution, and other sources of pollution need to be curtailed, or turned into sources of waste.

Information about pollution from the fossil fuel energy system and from the extraction systems, provide a major driver for energy transformation, partly because this issue seems ‘economically’ politically and energetically solvable, while other sources of pollution seem more difficult to deal with.

However, even facing the problem, provokes a likely politicisation of the information system. How would people, in general, become aware of pollution and who primarily suffers from its effects, especially when it threatens established systems of power?

What people become aware of, what can be understood or done depends on the Information System. This system determines what feedback is available to conscious humans, about what is happening in general. The information system, in theory, could allow humans to recognise eco-feedback in response to systems such as waste and pollution, or extraction. Information is vital to social functioning, and part of social functioning. Accurate information is even more useful.

Unfortunately, information about complex systems, such as societies or ecologies, is almost always limited and inadequate. Some information may tend to be symbolised rather than literal, because of the difficulties of representing the information in a literal form (these difficulties can be political as much as in terms of human capacity).

Information systems can also hide, or distort, ecological feedback, because of flaws in their design, or because powerful people do not want it to bring the problems to general attention. This adds to confusion, and to the possibilities, that the information system primarily reflects human psychological projection, fantasy and shadow politics.

The political and economic systems also directly impact on the information systems, as politics often centres on propagation of politically or economically favourable information and the inhibition of politically unfavourable or economically information. Economic power, ownership and control of sources of information can also influence what information is collected, processed and made widely available.

Information is not so much ‘received’ as interpreted, so Cosmologies and politics which provide a framework for interpretation, play a big part in how the information is interpreted and, then, what kind of information is transmitted.

Government, Religious, Economic, or military (etc) regulation can be a further important part of both the information and political systems, sometimes affecting what is likely to be transmitted. Information systems, in turn, indicate the availability or coherence of regulation and the understanding of problems and predicaments. Regulation is based on information selection as well as political allegiance, and regulations can be opaque, or hidden, as well as easily decodable. For example, until recently it seemed very difficult to find out what the NSW governments regulations for Renewable Energy Zones, meant in terms of business, building, or connection to the wider system.

The information system does not have to be coherent, thus we can be both informed and disinformed of the progress of climate change and energy transformation by the system. Certain groups are more likely to be informed than others, even though everyone tends to frame themselves as being well informed – especially in an ‘information society’ when being well informed is a matter of status. Information does not have to be accurate to have an effect, it is also part of socially constructed propaganda – as we can see with climate and covid denial, and this can influence political process, victories and inaction.

In summary, most information distortion comes from: economic functions such as business hype, secrecy and deception; from organisational functions such as hierarchy, silo-isation, lack of connection and channels; from politics where information is distorted for strategic advantage; and from the complexity of the systems that the information tries to describe and the inadequacy of the language or approach being used.

Technological systems enable the kind of energy use, direction and availability, a society can have, the kinds of extraction it can engage in, the range at which political and economic systems can have an effect, the modes of transmission of information, and the types of waste pollution and dispersion which are likely to happen. Technologies also necessarily use properties of the environment and ecologies around them in order to work, and thus interact with those environments and again cause unintended consequences.

People use technology to extend their power over others, extend their capacity, escape regulation, or render previous technologies less dominant, and hence technologies tend to be caught in struggles between groups, thus provoking unintended social consequences.

We could hypothesise that technologies, as used under capitalism (and perhaps elsewhere), tend to extract people out of their environment, and break the intimacy between humans and ecology, or shift human perception onto the technology rather than the world, therefore making it easier to regularly engage in processes of destruction.

In the contemporary world, technologies become objects of fantasy, and metaphors by which we think about the cosmos in general. For example the clockwork universe is now almost replaced by the information processing universe.

Finally we have planetary boundaries. The planetary boundaries are ways of conceiving the limits and constitution of ecosystems, and are, as such, fairly abstract. These boundaries represent systems necessary for human and planetary functioning.

They do not necessarily form the one system, and can be separated out for purposes of analysis. They act as guidelines, and probable reactive limits which are essential for the consideration of ‘eco-social’ relations, and the likely long term success of those relations. Measuring the boundaries may have a wide margin of error, as due to the complexity of these systems and their interactions. We will not know for sure when they will collapse until they do, and once they start collapsing they will affect the resilience of other boundaries. So the known limits on the boundaries will change as we take more notice of them, and keep challenging them.

Exceeding the boundaries almost certainly leads to the rundown, or breakdown, of ecological functioning, and this breakdown then adds difficulties to maintaining other systems. If they are maintained ‘artificially’ then this requires extra energy expenditure, and may have further consequences. Kate Raworth’s ‘donut economics’ presents a quick and easy way of conceiving functional economies in terms of ecological boundaries and human betterment [1], [2], [3].

Any global system which does not preserve or reinforce planetary systems will probably give impetus to global ecological collapse.

The systems are usually listed as involving: climatic stability, biospheric integrity (distribution and interaction between lifeforms, balance between species, rates of extinction etc), water flows and cycles (availability of drinkable, non-poisonous water, and water for general ecological functioning), biochemical flows (phosphorus and nitrogen cycles, dispersal of valuable materials which literally form the ‘metabolic rift’, etc), ocean acidity or alkalinity (which affects the life of coral reefs, plankton and so on), levels of particulates or micro-particulates (which poison life forms), ozone levels, and the introduction of novel entities into the global ecology and their unknown systemic consequences (new chemicals, plastics, microplastics etc.). [4]

It is the functioning and disruption of these boundary systems which make processes of pollution and extraction problematic. Thus they impact directly on society, and appear to limit the kinds of economic growth, extraction, energy and technological systems that can be deployed safely.

Capitalism and developmentalism tend to recognise boundaries only to ignore them, and claim that ingenuity and willpower, will overcome those boundaries forever without limit.

Then we have Geographic systems as a subset of planetary boundaries. Geography affects the layout of energy systems, the potential reach of political and economic systems, the ‘natural’ flow of air and water, changes in temperature, the availability of sunlight, and the kinds of extractions which are ‘economic’ or economic in the short term, but deleterious in the long term. Geography is relational, giving layout in space between spaces and constructions. Geography shapes and is shaped by politics, social activity, economics, pollution and so on.

Mountain ranges, forests, plains etc may affect the layout of Renewable Energy, or the RE may affect the land, if trees are felled, fields converted etc. Wind may be severe, putting a limit on size of turbines, or the angles of solar panels. Winter darkness, or heavy seasonal rain can affect the possibilities of solar power.

Geography constitutes the human sense of home, and transformation of geography or relations of geography can produce a sense of ‘unhoming’, or dislocation in place and in the future of place.

Recognition of the interactions of these systems, with their differing but interacting imperatives, seems vital to getting a whole and accurate picture of the problems and opportunities presented by energy transition.

All the systems that have been discussed here, are complex systems. They are composed of ‘nodes’ which modify themselves or change their responses in response to changes in the ‘system as a whole.’ The systems are unpredictable in specific. The further into the future that we imagine, the less likely our predictions are to be specifically accurate. We can, for example, predict that weather will get more tumultuous in general as we keep destroying the ecology, but we cannot predict the exact weather at any distance. Complex systems produce surprise and actions often have unexpected consequences. If we seek to apply a policy, we cannot expect it to work exactly as we think it should. For example, the political move to make ‘markets,’ the most important institution, did not deliver either efficiency or liberty, as was expected, almost the opposite in fact. In all cases of actions within complex systems we should seek for unintended consequences. Sometimes the only realistic way to approach unintended consequences is to realise that our theory could not predict those events, and without looking we might never even have seen the events, or realised their connection to what we did. Working in complex systems, all politics becomes experimental.

While complex systems adapt or seek balance, they do not have to arrive at the best conditions for human beings. From a human point of view, they can be maladaptive. For example, a social system can be maladaptive and destructive of our means of living. The ecology could arrive at a balance within which many humans could not live.

People involved in promoting Energy Transformation have to deal with the various complex systems we have discussed above. The complexity does not mean we cannot make any predictions, although we need to treat them cautiously.

There are a number of different theories about the Capitalist States.

The standard Libertarian argument seems to be that you just roll back, or get rid of, the State and all wealthy capitalists will renounce their privilege and let everyone else live in liberty and prosperity, untroubled by the inequalities of power and wealth that may arise.

The slightly more conventional, capitalist theory is that the State is needed to enforce property rights, enforce contracts, while providing a relatively neutral legal framework to solve disputes among the powerful, and defend against foreign states. Possibly the State should also stabilise things after massive market failure. Although there seem to be some who do not seem to believe the market can ever fail so, in their view, this is not needed. This is more or less the standard official neoliberal position; with the addenda that the State should be as small as possible. As suggested elsewhere in this blog, the actual neoliberal position seems to be that the State should defend the established corporate power and market structures against ‘democratic’ political change, or even natural change, because this is really important.

Other people see capitalism not as trade (trade goes on everywhere, even in communist states), but as a set of patterns of power relations built around particular organisations of extraction, production, distribution, and trade etc., which tend to favour the already wealthy (those with capital, or access to capital). Capitalism is not in any way, an inevitable ‘natural result’ of people engaging in exchange. Historically, capitalism has grown out of the violence of the slave trade, dispossession of people from their land, colonial depredation, forcing people to engage in trade. forcing people into wage labour, suppression of workers’ organisations, enforced occupational illness, environmental destruction and so on.

Capitalism tends to destroy self-sufficiency for most people, and throw them onto the labour market, where they are expected to obey a boss. It is not an inevitable model of liberty. Saying you can choose your boss, is bit like saying you can choose your master, or your State. This violence and destructiveness, generates a level of resistance by the population in general, and this resistance needs to be channeled into supporting the established systems of market and political power (perhaps through people like Trump).

If you have this view, then you will expect a capitalist state to slowly move towards plutocracy. In a plutocratic State, wealth buys politicians, laws, regulations, violence, the information which gets circulated, and so on, and hence (over time, as money can buy almost anything), the State becomes governed to benefit the ultra-wealthy. Corruption and ecological destruction become normalised. Wages stagnate. Economic crashes become regular affairs, and the established elite are bailed out from their mistakes. The Government subsidises the corporate sector, either directly or through military spending, etc. This all happens, because, in a capitalist world, that is clearly what the State is for. Ordinary people feel the State no longer listens to them or ignores them (and they are largely correct). This is more or less what we have today, after 40 years of ‘free market’ boosting.

This does not mean that all wealthy people share all interests in common. They may well fight over minor issues, but all sides largely aim to keep the State plutocratic, and to protect their wealth.

The set up aims to ensure that people think their best interests involve trying to go along with the established organisation, or that they can try to take advantage of this organisation for their own benefit.

The Capitalist State engages in planning so as to maintain the power of capital, as best it can.

If you were in favour of abolishing the State then you probably have to void all other sources of power, including wealth, as those people with wealth will get around to setting up a State over you, to defend and entrench themselves. If you were in favour of a minimal State then you probably also have to guard it from takeover by the wealth elite, or the religious elite, or techno elite, or the military elite etc….

It is hard to keep States relatively democratic, and no easier under capitalism, especially if the power of labour has been crushed, which is an aim of capitalism in general.

[This post is a slightly revised version of the original, and now deleted, end of the post Neoliberal Conspiracy 07]

Wealthy people do have power. The more wealth they have the more power they can exert if they choose to. The fewer non wealth based sources of power that are around, or are not phrased as businesses, the more power they can exert. They can buy all the other kinds of power from political representation and legislation, through violence, to communication and information. They can buy status, because they must have virtues if they are wealthy; they must be wealth generators for everyone, and deserve special privileges. Neoliberalism appears to both increase their power and hide opposition to that power. So wealth-power and neoliberalism fit together quite harmoniously or, as in a previous blog post, we can say that crony capitalism is normal capitalism, and neoliberalism intensifies crony capitalism.

It is not difficult to find the main propaganda points of neoliberal ideology in the media and elsewhere. It is widespread, although the analysis of what neoliberals actually do, and aim to achieve, is not. This lack is also significant.

Thus it is easy to find people extolling the virtues of business, the talents of business people, the centrality of ‘the economy’ to prosperity and freedom, the importance of growth, the importance of tax-cuts, the importance of cutting regulation, the importance of free markets, the connection of free markets to liberty, the idea that governments are always useless, the parasitic nature of people on welfare, the evils of socialism and the left, the evils of ‘greentape’, the need to encourage the economy whatever, and so on. Business news is expected, even if ordinary people don’t read it or watch it, union (marxist, or communitarian anarchist) news is not. Neoliberal ideas are widely and repetitively propagated. This is hardly surprising given corporate control of the media.

Thus not only do neoliberalism, crony capitalism and increasing the power of wealth (plutocracy) fit together but the main points of the ideology are so prevalent that they can be taken as ‘common sense.’ They can be referred to and accepted, without needing justification. They must be true. They can seem true a priori.

This does not mean the wealth elites are totally united. For instance, some of them don’t like Trump, even if he is carrying out most of the neoliberal programme, doing quite well at hiding it and cultivating passionate followers to help keep the project going. It is as equally possible they don’t like him because he defrauds other businesses and his word means nothing, as that they dislike him because he is doing something mysterious to benefit ordinary Americans, as is frequently alleged. Some people in dominant groups actually believe in climate change as well, but the media rarely explains why it is happening, and it usually reports climate change in a way suggesting its not that much of a problem for neoliberalism, or we just need to act as individuals. This is the more humanistic version of the conspiracy in action. The result is much the same; maintaining elite wealth and power comes before dealing with climate.

All this implies, the idea of Neoliberal conspiracy is plausible.

On the other hand, Neoliberals tend to explain the current crisis of democracy in terms of ‘government,’ which they control but pretend is controlled by others. These controlling and malevolent others appear to include ‘cultural marxists,’ ‘critical race theorists’, postmodernists, socialists or whatever is today’s evil figure. The problems that we face result from some big and dangerous conspiracy of the Left, or are invented by the conspiratorial Left out of thin air (i.e. the climate fraud, the covid fraud, the Biden victory). This is heavily implausible.

I’ve no real idea what cultural marxism or critical race theory is, and I’m not sure the general public would understand the main points of these ideologies either, as put forward by their supposed proponents. These theories don’t seem as widely distributed and explained as they would be if they were important to a major power group. So, if these movements exist, they are clearly not being promoted by a particularly powerful or influential class. They are not widely taken for granted by people. And the general approach in the media, would seem to suggest that you can just say ‘Cultural Marxism,’ or ‘Critical Race theory’ and know that your audience will assume whoever is being associated with these theories must be evil, even if the audience don’t know what they are. Jordan Peterson seems to have made a career out of behaving like this.

From this alone, it seems likely that the opponents of these cultural marxists, whoever they are, have all the relevant power, or the strategy would not work.

[My initial hypothesis was the neoliberals and their supporters could not use the old horror of revolutionary Marxism, because it was nowadays so rare, and so they turned cultural criticism (which is a standard from of Western behaviour, since Plato or the Reformation, depending on your choice) into a dismissible evil, by calling it cultural Marxism. But then I remembered how a few people who got together to protect some protestors from attacks by fascists, became portrayed as a vast, violent and subversive movement who conveniently wore black clothes and supported Joe Biden. So the neoliberals could have pretended that revolutionary Marxists were still a problem, and perhaps by magnifying anti-fa they did.]

Academics, who I suppose are supposed to promote these things, don’t have much power. Universities are nowadays run as neoliberal business, with generally relatively high level business executives in charge (often such overt neoliberal ideologists as Maurice Newman). Universities nowadays aim to bring in money, not change the world. Academics frequently have to ally with the corporate classes for research money, so the days of investigative independence is fading. In Australia academics were among the only people not eligible for the highest government support if their jobs were made redundant by Covid. Again not a mark of power. So the chances are high that those who tell you academics are powerful are lying to cover their own power and give you a relatively powerless enemy to dislike.

Then I guess there are scientists. Obviously neoliberals will argue that scientists are less trustworthy than businesses or the hunches of demagogues (Trump is great at that). The idea seems to be that, if science clashes with neoliberalism, it is necessarily wrong, despite all the successful stuff it does elsewhere. I’m more than a bit skeptical about that position. This does not mean scientists cannot be wrong; they are human (just like neoliberals), but they are the best we have got at the moment, and science tends to be self-correcting. That is how it works, and it is also why scientists and doctors can seem to change their minds quite often; they are ideally persuaded by the evidence, and new evidence is always arising. Yes they defend the positions they are currently holding, but eventually those positions fade – they are not held to be true a priori, and beyond challenge, like neoliberal economics. Scientists are often persecuted by governments and businesses, who remove data from websites, sometimes from libraries, forbid them to talk, smear them when it is handy, or sack them if they don’t give the correct neoliberal response. So they don’t appear to have much that much power as a class. They often can’t even get people in power to consider the desperate state of the planetary ecology. They also don’t have political unity as a class, as there is no particular politics necessarily associated with physics, geology, biology or whatever. Science is not like economics, where neoliberalism will get you places.

There is less obvious basis for scientific power outside the corporate sector anymore, and that is likely subject to neoliberal control. This is why we should not particularly trust pharmaceutical companies, insecticide and genetic engineering companies and so on. They are less concerned with scientific truth than with profit, and in neoliberalism profit is the true measure of everything.

There are a few billionaires who run charities, like Bill Gates and George Soros, and a few tech billionaires who routinely get blamed for the crisis and for deep conspiracies. But the odd thing is that the billionaire class is generally not mentioned as a class, and most members are not named. The people who attack Gates and Soros, rarely attack Rupert Murdoch even though he is clearly political and heavily involved in determining contemporary policies and issuing propaganda. They don’t furiously attack Meg Whitman, Jim Justice, Bill Haslam, Silvio Berlusconi, Suleiman Kerimov, Gautam Adani, Clive Palmer, Gina Rinehart, Sheldon and Miriam Adelson, Tom Steyer, Tommy Hicks Jr, Harold Glenn Hamm, Charles Schwab, Paul Elliott Singer, Joe Ricketts, Betsy DeVos, Linda McMahon, or Charles Koch (founder of the Cato Institute, Americans for Prosperity Foundation, Freedom Partners and the Koch Network) just to give a few names directly involved in political influencing unlike Bill Gates. Most people probably do not know many other billionaire’s names as they stay out of the media. We can conclude that while the billionaire influence on politics is pronounced, the neoliberal denunciation is highly selective.

Then of course there are those people protesting against being shot by police. This is obviously such a vast and powerful conspiracy they can’t even get the police to stop killing them, and the Republicans can just ignore them as they have such little influence, and some Republicans can support people who shoot at them, or drive into them. Not much ability for masses of evil power there, even if a few statues do get toppled.

Then there are the socialists. Well the Right fusses about them, but I haven’t seen nationalisation, as opposed to privatisation, of an industry for quite a while. In the US getting a general basic wage that people can live on, has not happened, and does not seem to have much hope of success. The US can’t even get a health system which does not bankrupt sick poor people, no matter how much Trump promised he would fix it easily. Furthering control of government by the working classes rather than the corporate class seems to have failed all over the Western World. ‘Socialism’ seems generally used as a swear word, and calling some idea socialist is the supposed end of many arguments. Again this could not happen if socialists had any power.

Not surprisingly because the corporate sector control the media, ‘left wing’ thinking and action, is passively censored; it is hardly mentioned, other than by its opponents, who are not always that accurate in their descriptions. If you want to find out what the Greens stand for, for instance, then you have to go to the Greens, or perhaps approach some lonely person selling a weekly or monthly newspaper on a street corner. The Left does not control the mainstream media or normal talk, so this takes effort and most people cannot be bothered. Why would they be? they are constantly told the Left is evil and idiotic. To most people this is just the way things are, even if they think they have worked it out for themselves.

At the end of all this, we can see that according to neoliberals, the enemies of liberty are a few named billionaires (Gates and Soros) who don’t fully subscribe to neoliberal theory (the huge majority of billionaires can be ignored as they support the establishment, or at least don’t overtly attack it), a few largely disorganised protestors and a bundle of academics who have next to no power in a system devoted to promoting fake news. These people have little in common, other than being despised by neoliberal followers. They do not seem a plausible danger, and if they form a conspiracy it seems extremely badly run and powerless.

Comparing the two ideas, it seems to me, that the idea of neoliberal conspiracy easily wins the plausibility stakes.

This post continues to explore the apparent lack of consideration given to context in the basic axioms of Austrian economics; in this case culture and ecology.

Discussing purposeful action, which is supposedly basic to the economy, Rothbard goes on to argue that a human must have certain ideas about how to achieve their ends. Without those ideas there is little in the way of complex human purpose.

However, this sidesteps the issue of where does this person get the ideas from, as well as the language to think about those ideas? The ideas are unlikely to be purely self-generated, with no precursors. In reality, ideas arise through interconnection with other people and previously existing ideas. This of course does not mean people never have original ideas, but without interacting with other people it is doubtful they would have complex ideas or language at all. Indeed, the people they interact with may have a massive influence on the ideas, and approaches, available to the person. Ideas are socially transmitted.

Even our individuality is based in the groups we have encountered, the ways we categorise our selves in relationship to others, and the child rearing we experience. It is not as if we are born fully conscious and evaluative, able to deduce everything all by ourselves from first principles….

However, in response to criticism, Rothbard states: “We do not at all assume, as some critics of economics have charged, that individuals are ‘atoms’ isolated from one another.”

Where is the evidence of this recognition in the initial axioms, from which all else is derived? Its certainly not clear to me that this recognition exists, other than to be wheeled in to get rid of objections. “You think people are isolated from each other” “No we don’t. I mention this in a footnote.” This recognition seems an add on – whereas it seems more likely that humans are both individual and collective from birth onwards. To some extent we can even say that humans have the capacity to learn to be individuals, to individuate, but it is not always easy.

I suspect that if we included culture’s (and social organisation’s) effects on exchange and economic action, then we might not be able to perform a supposed universal justification for capitalism, and its exemption from attempts to control it or regulate it to be less harmful. And this justification and protection, seems to be the purposeful action of Austrian economics from its beginning.

All action takes place within a web of actions – which is sometimes known as an ‘interactive network,’ or a ‘set of complex systems’ and sometimes, in Austrian economics, as a catallaxy, or as Hayek says “the order brought about by the mutual adjustment of many individual economies in a market.”

It is possible that, with this term, Hayek is pointing towards what is now known as “emergent order,” which involves far more than just ‘individual economies,’ adjusting in a ‘market’ – as markets cannot be separated from other processes, including social and ecological process which also adjust to each other.

While it is often assumed to be the case, it should be noted that the ‘order’ which emerges from a complex system or ‘catallaxy’, does not have to be hospitable to humans. Historically we can observer that the ecological order is often changed by humans disasterously and, as a result, humans can no longer flourish in those new ecological orders.

Sometimes this ecological collapse occurs because some form of behaviour which once helped survival has been intensified to a level at which it:

Hayek’s formulation uses the cultural assumption that order is ‘good’ for humans, to imply the market always brings ‘good’ results, when it may not, even if the ‘order’ arises ‘spontaneously’.

Economies occur within general ecologies: they can be said to be context dependent. An impoverished ecology is likely to produce an impoverished economy for most people, even if the wealthy are very wealthy and well provided for.

Rothbard states on page 4: “With reference to any given act, the environment external to the individual may be divided into two parts: those elements which he believes he cannot control and must leave unchanged, and those which he can alter (or rather, thinks he can alter) to arrive at his ends”.

Earlier he talks about rearranging elements of the environment…

All this suggests that Rothbard thinks of the environment as a largely passive backdrop to human action, not a participant in that action, or even likely to react to that action. The environment is portrayed as essentially passive or dead, or humanly controllable, neither of which seem to be the case. Again the aim seems to be to reduce everything to the human individual, who determines what is to be done.

The approach not only does not recognise the importance of groups but appears to be anti-ecological, or anti the recognition of the necessity, and force, of ecological processes. This could be accidental, but perhaps it occurs because neoliberalism grew up to be anti-ecological in the roots of its thinking (thinking that humans are detached from each other and the world), perhaps because social movements recognising the importance of ecologies were seen as a threat to corporate profit and liberty, or perhaps it is just their overconfidence in the culturally backed idea of human specialness and isolation.

Rothbards adds that acts involve means, and this involve technological ideas. Both true, but forms of government and organisation can also be thought of as technologies. It is easier to hunt with hand weapons if we organise to hunt together, and use strategy and planning in that hunt.

“In the external environment, the general conditions cannot be the objects of any human action; only the means can be employed in action.”

I’m not sure what this means, but it seems to be suggesting that we cannot work with environments….

However, economies are enmeshed in environments. Economies do not exist without ecologies and, at the moment, without naturally livable ecologies. (Possibly in the future large numbers of humans may be able to live in purely constructed environments, but not now).

We have to grow food, we have to survive climate, we have to survive in the atmosphere, we need drinkable water, we need ‘raw materials’, we need energy supplies (more than just food and water if we are going to survive with any technological complexity). We need functional waste recycling systems and pollution processing, and so on.

If ecologies are destroyed then economies are highly likely to collapse, and in any case the aim of the economy becomes reduced to survival, and radically simplifies. Social support and social action is still vitally important.

Economies are also enmeshed in environments of social and political life, as people attempt to use rhetoric and persuasion and sometimes violence to protect their markets, regulate and structure the markets and so on. Wealth, earned on markets, gives power and that power is used to ensconce and intensify the position of the wealthy. At the least, all economies are political economies, in the sense that economic action involves politics and vice versa.

It seems to be the case, that extracting something called an economy from both social and ecological life, is a massive and probably dangerous over-simplification.

In these last two posts on praxeology, I have implied you cannot ignore history or social studies to formulate a study of economics, because that forms the conscious (or unconscious) data you draw your a prioris from. I’m not asserting that a prioris of any kind do not exist, they may, but it seems unlikely that social science a prioris exist, and that the a prioris of Austrian economics are inadequate and dependent upon unacknowledged (or unconscious) cultural foundations.

Let us reformulate the initial propositions as simply as possible, from the discussion above.

This post starts to look at praxeology as politics, with the hope of making some more accurate starting points in a second post about the left out background of Austrian economics. In these two posts, I move on from Mises to the first few pages of Murray Rothbard’s Man Economy and State – to show that Mises was not an aberration.

On page 1 Rothbard begins his recapitulation of Austrian praxeology by stating: “Human action is defined simply as purposeful behavior”.

We probably should add, as necessary and fundamental and relatively well known, that the purpose can, but may not, have much to do with the result. The world is not easy to control (which is a point free market people often make), although people do often attempt to control it. We cannot deny attempts at control exist and are normal or routine, and that they often fail or apparently make things worse.

Unintended consequences are normal.

If people do have unconscious processes, then they may well be unaware of the real purpose behind their action, and suggest something socially appropriate instead as their purpose, as can happen with post-hypnotic suggestion.

A purpose may include targets such to make more profit, or to control the market (or people in the market), as well as possible. Purposiveness can also include lying, or mistaken ideas.

People often have the purpose of trying to influence, or sway, other people’s behaviour – which is one mode of attempting control.

Markets also involve the building of trust and connection, as the more likely people feel connection and trust the more likely they will purchase, and pay back. So markets involve purposive social action.

Everyone may know these factors already, but let us put them up front.

“Human action… can be meaningfully interpreted by other men.” The interpretation by those “other men” does not have to be correct, but there will be some shared (although not uniform) cultural ways of interpreting behaviour, and similarly shared, but not uniform, expectations about human behaviour, which people can use to make interpretations.

Different people, in different groups, may interpret observed behaviour differently. This is clearly observable in the way different groups interpret Donald Trump’s behaviour. Some people almost always excuse it, say he is doing wonderful things, that his statements are not literal (or are aimed at owning liberals) or claim that much of the information about him is fake news, and some people see the behaviour as constituting a selection of abominable, corrupt, incompetent, conflictual and self-seeking or self-pleasuring behaviour.

Is it possible to suggest people respond to their interpretation of other’s behaviour more than they react to the behaviour itself? Economics (amongst other ideas), provides tools for interpreting human behaviour and human actions. Inadequate tools will probably produce inadequate interpretations, and the strategic ignorance of certain facts. As such economics can risk becoming a part of political rhetoric, rather than a quest for testable knowledge – especially when it denies that its axioms need no testing for accuracy.

So, do we understand these processes of purpose and interpretation properly, and apply them to what we are doing, or do we pretend we always have direct, and unmediated, access to truth?

Means and motives, are not purely individual constructions. They may well be culturally specified, or limited. People are ‘thrown’ into an environment not entirely of their own making, or resulting from forethought. This is important. Not everyone may want to make a fortune, or be able to make one, and that realisation is probably needed for some kinds of economic analysis. It is unclear what ‘profit’ might mean to everyone, and I suspect that Austrian economics would admit that, but make it secondary.

Economic actions blend into other actions.

Rothbard tells us the “fundamental truth” of Praxeology is that people act. Fair enough. However, this statement that people act, is then shifted into a more dubious proposition.

“The first truth to be discovered about human action is that it can be undertaken only by individual ‘actors.’ Only individuals have ends and can act to attain them.”

Indeed individual actors can and do act. People can act to undermine the groups they belong to. No question of that. But can we really dismiss social groups, and the social background, as of no fundamental, or a priori, importance?

Do groups of people never decide to act together for certain ends? The answer to that would seem to be ‘Yes. It happens all the time.’

Recognising that people make decisions in groups, and act together, does not mean that everyone is necessarily submerged in some kind of immaterial group mind, or that people think the same thing and have the same abilities. Or that individuals always get pushed into doing things. It means they cooperated, and supported each other, to a degree. Neither does it mean that people only belong in the one group at the one time….

On page 3 Rothbard asserts “‘groups’ have no independent existence aside from the actions of their individual members.” Yet the coordination of groups gives the possibility of an effect greater than the sum of its parts, and which sometimes changes the possibility of action considerably. Indeed the reason why people act together is known to Mises; acting together has the potential to produce greater effects, or even previously impossible effects. The buzz term nowadays is ‘synergy.’

Groups also can have existence beyond individuals. Groups frequently continue to exist, or manage to maintain some kind of continuity and identity, despite an ongoing slow and complete change of membership. If a group is just individuals, then this happening should probably not be quite as common as it appears to be.

It is commonly remarked that people do ‘bad actions’ when in groups they may not have done alone. If so, then the group is changing their behaviour; the individual’s action may go into a different ‘dynamic’, or the groups produces different motives and means of action for individuals.

A useful and relatively accurate economics should probably involve the study of some of these group effects and group dynamics, as well as individual effects and dynamics.

It would seem to be a possible a priori that humans are both based in groups and individuality, so the analysis needs to go in both directions, to groups and to individuals.

Purposeful behaviour almost always involves humans acting with or against other humans, human groups, and environments – often several at the same time.

As said earlier, studying this bifold nature of action (individual and collective), is often difficult to analyse of describe, but difficulty does not mean that the fact is not real, or should be abandoned at the base of analysis.

It seems to be that the idea of Austrian economics, is to eliminate consideration of these complex effects, on the grounds that simplification is not just distortion, and that the complex effects and uncertainties can be explained purely through considering simple units in combination.

The political consequences of this step just happen to favour corporate and business groups, by ‘pure accident’ (actually this political consequence will probably be denied).

I suspect that one idea underlying all of this apparently oddly deficient thinking, is to make formal ‘government’ something unnatural, rather than something people do all the time.

As implied above, many groups exist with some kind of decision making process. They have some expectations of loyalty, some purposes, some social control? Probably most – especially those important to an individual.

Corporation and businesses rarely exist without some mode of organisation, and some mode of government. They have ways of making decisions about action, about what people lower down the hierarchy should do, about motives, about ends that affects the individuals involved which may change those individuals.

Indeed, I cannot remember ever seeing a free market person, no matter how hostile to government, who objects to a corporations governing its members – even if there is not the slightest attempt at democracy or representation.

Teaming up amongst the lower orders is to be discouraged, especially if it is team-up against the true elites, while it appears that team-ups amongst the hyper-wealthy is to be ignored, or blamed on ‘the government’ which is defined as having nothing to do with, or no dependence on, those hyper-wealthy people and their organisations.

Attempts at organising to achieve group and individual ends seem pretty fundamental, and it is questionable if the effects of this organising can always be reduced simply to individual motives.

The proposition that groups can be methodologically (?) reduced to individuals has the function of making it non normative for people to think of teaming up together to combat the real power of corporations, as all ‘real ethical people’ are pure individuals – even the corporation is just individuals and does not exist, and it has no drives of its own.

This psuedo individualism allows a person who goes along with neoliberalism to think they are proudly individual by going along with it – which in Rothbard’s society is great praise. “I’m an individual because I’m a free market person.”

We could hypothesise that people who believe people are naturally self focused, or have a limited range of sympathy (say limited to their family) might tend to behave more selfishly like they think everyone else does. It becomes a mode of interpreting what others do, which is self reinforcing. Given these assumptions, we have to defend against the self-focus of others, and can’t expect help from others in our groups.

This brings forward the issue that by prescribing how people act, economics is also making ethical claims as to how people should act. It is becoming a primarily political tool. I’d expect all social theory to act as a political tool, as well as a tool for understanding, but it should probably not deny this, as it should not begin by lying, and it should not make lying its end – the end is to be as realistic as possible. But, as ethical statements, these point have no, or carry no, compulsion.

Thus Austrian economics claims people should act as individuals, should shun government, and should leave life to both the market and those who attempt to control the market to benefit the corporate business sector. Established profit is the only good. People who fail, in a free market, are inadequate and deserve only what they get. People who help other people for no return are stupid or corrupting those people, so it should not happen. Free markets do not emphasise virtue, just abstinence from protest. That appears to be the Austrian ethical life.

It might be a bone fide political or ethical objective to convince people that they are individuals living purely in contractual agreements (even if they have never agreed to a contract in their lives), but it is not necessarily descriptive of a priori ‘human nature’. It is also a political act, so it is situated in relationship to other people from the beginning.

We would expect the neoliberal abolition of the recognition of groups as a basic form of life, would mean that they would disapprove of corporate personhood, and the effective diffusion of responsibility in corporations. That is, they should insist it is not the corporation which makes decisions and which takes responsibility, but individuals; from the deciders in management, or on the board of directors, to the people who carry out the instructions, and to the shareholders who provided the capital and who aim to profit from the companies decisions. If a company commits harm, then people should not be able to hide behind the company, or the excuse of obeying orders. They are, and should be, responsible for their actions, and be held to account. However, as we cannot ignore the company structure, the higher the management that approved the action, or ignored the action, then the more responsible the people should be.

I personally do not know what the free marketeer position on this matter is, at the moment. Hopefully I will find out. If the movement is primarily about benefitting corporate power, then it will protect those who benefit from that power and wealth, and shift responsibility away from them, or downwards, perhaps even to those who are hurt or harmed.

Ignoring voluntary and compelled co-operation between people might lead to as fundamentally a wrong set of assumptions and governance, as those which ignored voluntary (and compelled) competition.

Ignoring the power of groups, the basis of human life in social groups, and reducing human life through methodological individualism does help simplicity, but it does not help accuracy. We have to be aware of the background to the existence of individual action if we want to understand a collective process like the economy or social life.

In the next post I will further discuss the missing social and ecological background in more detail, and then propose some new starting points.

This is a continuation of the previous post on ‘Praxeology’. But its self-sufficient, you don’t have to read the other post.

This post is just a series of questions about markets to those who believe in the possible existence of ‘free markets’ and the virtues of corporate ‘free markets’. The indented parts are usually comments on the questions.

Does wealth give power? Does this power increase with increasing inequalities of wealth?

Does capitalism magnify differences in wealth? Does it lead to accumulation of differences in wealth? [Perhaps due to inheritance laws?]

Do wealthy people and businesses normally team up to get even more co-ordinated power and market control?

Do some corporations currently have assets and resources greater than some countries?

Do corporations and wealthy people get priority access to politicians and government, to put their views on how governments should behave?

Does wealth buy lobbyists, whose job is to influence government policies?

Does wealth enable the wealthy to buy politicians through donations of money and labour to the campaigns of those politicians, or by promising well paid easy jobs to them after they retire from politics?

Does wealth allow people to fund the semblance of political activity, and give a false impression of what is popular?

Do Big business and government naturally ally? Who is likely to be dominant and under what circumstances?

Does wealth buy positive ‘information’ through the funding of think tanks, or university research centres, which primarily exist to justify ideology and research which supports the interests of wealth?