Climate change and ecological destruction are often framed as ethical challenges, to be solved by a new ethics or a better notion of justice. While I agree that ecological destruction is an ethical challenge, I suggest that this means it will not be solved in the time frame available.

This occurs for four reasons. First there is no basis for ethics which is not already ethical; therefore it is highly improbable we can have an agreed ethics take form across the globe in the needed time frame. Second, we live in complex systems which are unpredictable and not completely knowable, so the results of ethically intended actions are uncertain. Third we influence the meaning of what is good or bad through the context we perceive or bring to the events; given complexity and given cultural variety, the chances of agreeing on a context for these acts and events is small. Four, because context is important and caught in group-dynamics, ethics always gets caught up in the politics between groups, is influenced by those politics and their history, and there is no non-political space in which to discuss ecological destruction.

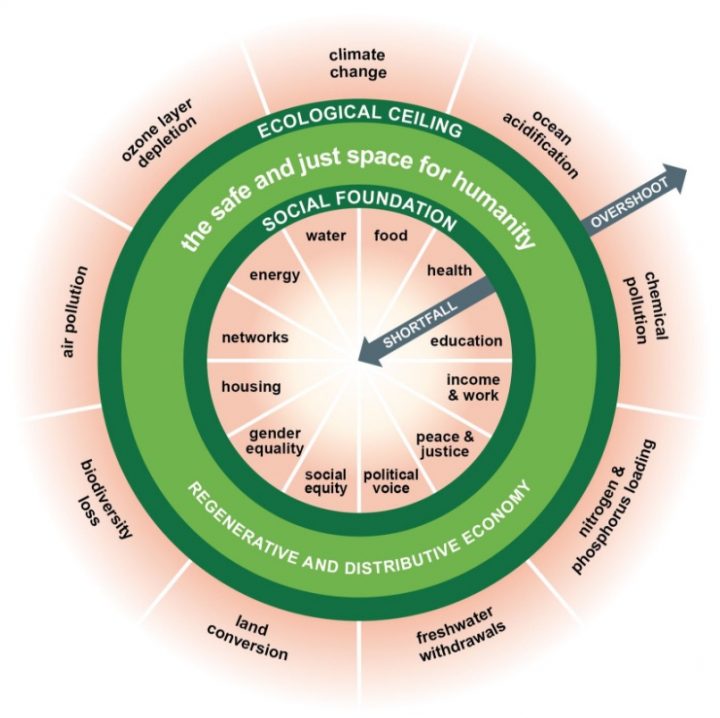

I prefer to talk about ‘ecological destruction’ rather than ‘climate change’ because, while people can disagree about climate change, there is less chance of disagreement about ecological destruction: it is pretty obvious, almost everywhere, with new highways, new dense housing, destruction of agricultural fields, destruction of forests, accumulation of waste, pollution of seas and over-fishing. We face far more ecological challenges than just climate change. Climate change is a subset of the consequences of ecological destruction and the dumping of products defined as waste, into the air, the ocean or vital water tables. The fact that we live in complex systems also means that deleterious effects in one system, spill out into others, and eventually cannot be kept local; we all interact with each other and the rest of the ecology. Everything is interdependent. Without plants we cannot survive. Without drinkable water we cannot survive. Without breathable air we cannot survive. These are basics for almost everything on earth.

However, given climate change is a moral issue, this decline in human liveability is not necessarily a bad thing. You have to already take the moral position that human survival, or that not harming fellow humans (in some circumstances), is good or the basis of virtue. You could decide that humans should be eliminated for the greater good; that they (or a subset of humans) are destructive parasites who should be exterminated. You might decide that only those humans with some qualification (intelligence, religious purity, dedication to the party, or wealthy, for example) should survive as they are ‘the best’ and the exemplification of what is moral. This is not unusual, most ethical systems do discriminate ethically between different people. Children do not have exactly the same ‘rights and responsibilities’ as adults. People defined as immoral or criminal usually face sanctions, and lessened ethical responsibility from the virtuous – indeed the virtuous may have be said to have the responsibility to harm the immoral.

No moral basis

If human survival is not a fundamental part of morality, then what is? ‘Care?’ why should care be thought of as good? Some moralities argue that care is a corruption, that care encourages bad habits and laziness, or that true care involves violently correcting behaviour defined as ‘bad’. Care is already a moral proposition, not the beginning of a morality. ‘Obedience to God’s rules?’ Assuming that we could agree on what God’s rules were, then why is obedience to God good? Could it be that God is a tyrant and we need to disobey to discover moral reality? Could it be that God expects us to solve problems ourselves, as the rules presumably have a basis other than the mere whim of God – if not why should we assume that whim is good? The idea that we should obey God is already a moral proposition. ‘We should do our best?’ Sounds great, but what is ‘best?’ Is our version of the best, actually the best? what if someone else says it is not the best, or their best contradicts ours? Why does following our inner guide/instincts lead to the best – what if it does not? Should we bring ‘the greatest good to the greatest number?’ leaving aside that this does not resolve what is good, then why is it good to consider the greatest number? Perhaps some minorities need a good that conflicts with the good of the greatest number? Again the proposition assumes the moral position that the more people gain the good, then the better it is – which could be ethically challengeable. Some other people think that taking good and evil as undecidable and therefor not worrying about it is the root of virtue, but who decides this is good? What evidence is there that personal peace is better than personal indecision? Valuing personal peace above all else, is already a moral proposition. Some people may even define what appears as ecological destruction as ecological improvement, partly because it is bringing the natural world under human control. What is destructive or not, is in itself an ethical question which runs into this problem of ethical presuppositions.

There is no way of resolving these dilemmas that I am aware of, and the presence of differing moralities and irresolvable questions, seems to demonstrate this. Moral uniformity, historically seems to depend on violence, and why should we accept that as good?

Complexity

In complexity we have multitudes of interactive systems which interact with each other. Nodes in these systems are constantly being modified by other nodes and events in the systems, or they are modifying their own behaviour and responses to events in the system. Sometimes the modifications are successful, or relatively harmless, and the new shape continues, sometimes they fail and it dies out. This is the basis of evolution, which happens all the time – there is no stability to ecologies.

The multitude of these links between nodes, are usually beyond full comprehension or enumeration by humans. Such systems are constantly in flux, often around recurrent positions, but they are open to sudden, rapid and unexpected change.

Complexity means that we cannot always predict the result of specific actions, especially when other people (and their reactions, and their attempts to ‘game’ the system) are involved, and when the situation is constantly changing and old points of balance are shifting. This change is something we face with ecological destruction. Patterns cannot remains stable. We can predict trends such as the more average global temperature increases, the more unstable the weather, and the more likely that violent weather events will occur. Similarly, the more destruction the more the unstable the ecology will become, and the more pollution the more unstable the ecology will become – unless it reaches the temporary stability of death.

Because so many events occur, are connected and are simultaneous, it may be impossible to tell what the full results of any particular action are. This is often expressed in the metaphor of the butterfly’s wing flaps eventually leading a major storm. Normally we would expect the multitude of butterfly actions to cancel each other out, and they may well do this most of the time, but not always. The reality is that small events can have major consequences, and we probably cannot tell which small events are significant until after the results have occurred. This lack of predictability means that we never have full control over complex system, we always have to adjust our actions given what occurs, should we try and work with the system.

This has particular consequences for ethics, in that the results of ethical actions, and ethical rules will not be predictable. The actions may be well-intentioned, but unexpected consequences are normal. If the consequences of an ethical action cannot be predicted, then how can it be guaranteed to be ethical? You can state that an ethical action is ethical irrespective of its results, but this is already an ethical position, and most people would probably not be completely indifferent to the results of their actions. The flux also means that propositions like the “categorical imperative” do not work, because we cannot assume situations are ‘the same’ or similar even in principle. Complexity means we cannot behave as we would want all others to behave in the same situation, because the situation could be unique. Besides perhaps different classes of people should behave with different intentions and different ethics. Why should ethics be uniform? Uniformity is already a moral decision.

Arguments about the results of actions and the similarity of situations are more or less inevitable.

Context

What this last statement implies is that the context of an event influences our understanding of the event. This is particularly the case given that we do not know all the connections and all the possible responses that parts of the system may make. We cannot list them all. We are always only partially understanding of the world we are living in, and this is influenced by the context we bring to those events. Possible contexts are modified by peoples’ connections to the events, and the cultural repertoire of possible responses and languages they have available. Given the 1000s of different cultures on Earth, and the multitude of different ways people are connected to the events and the people involved, then the possibility of agreement is low.

Politics

One important context is political conflict. One way of giving an ethical statement, ethical decision making, or an event, context is to frame it by your relationship to the people involved. If they are people you identify with, or consider an exemplar of what humans should be, then their statements are more persuasive and they are more likely to seem ethically good to you. If they seem outsiders or people you don’t identify with, or seem to be an exemplar of an out-group, then the less persuasive they will appear to be. Consequently ethics in always entangled in group conflict and group politics. This politics pre-exists and the groups involved may have different relationships to ecological destruction, and so have different politics towards that destruction, and towards other groups involved. Thus we frequently see people in favour of fossil fuels argue that developing countries need fossil fuels to develop, and that preventing the ecological destruction which comes with fossil fuels, prevents that development, and retains people in dire poverty and misery. What ethical right do already developed countries have to do that? What makes this poverty good? in this case developed countries may be considered evil for being concerned about ecology. Similarly developed countries may argue that most of the true destructiveness comes during development, and that while they are stabilising or reducing destruction, the level of destruction from developing countries will destroy us all. In this context, developing countries are wrong, or provide an excuse for inaction. The situation is already caught in the struggles for political dominance and safety in the world, as one reason for development is military security and a refusal to be dominated by the developed world again. There is a history of colonial despoliation involved here – although again to others, the despoliation can be defined (ethically) as bringing prosperity and development.

‘Climate Justice’, does not solve these problems because, in practice, justice involves defining some people as evil (which automatically sets up politics), it cannot limit contexts, and the machinery of justice depends on violence or the threat of violence. If a person is defined as a criminal and either punished or forced to make recompense, that occurs because of the potential of the powerful to use violence to enforce the sentence. In the current world system, there is no organisation or collection of organisations, which can impose penalties, or generate a collective agreement on what justice is in all circumstances, for the kinds of reasons we discussed above. Climate Justice is simply likely to encourage more blame allocation and conflict.

Recap and conclusion

Ecological destruction is embedded in ethical interpretations. These ethical interpretations are influenced by, and undermined by:

Thus it is extremely unlikely that we will spontaneously develop a universal ethical system which will allow us to decide what actions to take to resolve ecological destruction, or stop ecological destruction. Indeed the ethical conflicts will probably further delay our ability to respond.

Ethics may well be the death of us.