Continuing the series from the previous post….

Of these two political and economic movements (Neoliberalism and Developmentalism), Developmentalism is the oldest, but has since the 1980s been blended with Neoliberalism. As powerful movements and ideas, they can form obstacles to transition.

Developmentalism

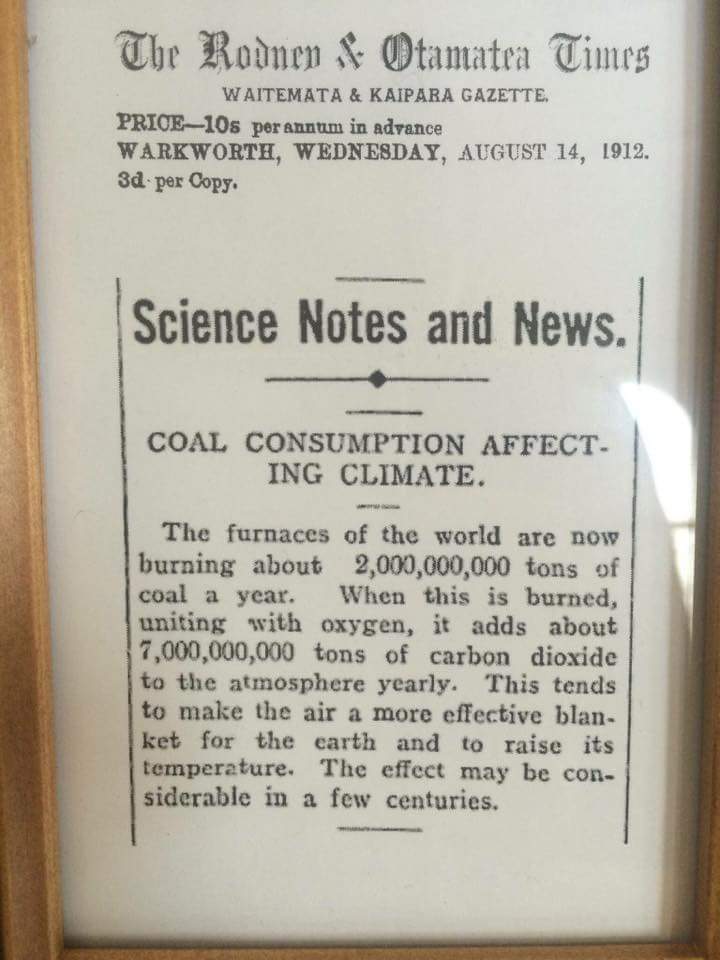

Developmentalism can be argued to have its origin in the UK with coal-powered industrialisation and mass steel manufacture, which formed a reinforcing positive feedback loop; steel manufacture helped implement industrialization and also increased military capacity to allow plunder of resources from colonies. Industrialization helped increase demand for steel. Fossil fuel energy was cheap with a high Energy Return on Energy Input. This loop provided a model for the ‘development’ of other countries, partially to protect themselves from possible British incursion.

While the UK’s development was developed alongside and with capitalism, capitalism was not essential for development, as was shown by developmentalism elsewhere. The earliest deliberate developmentalism was probably in Bismark’s Germany, followed by Meiji Japan, neither of which were capitalist in any orthodox sense. Japan rapidly became a major military power defeating both Russia and China. Revolutionary Russia also pursued developmentalism, and after the second world war developmentalism took off in the ex-colonial world becoming the more or less universal model for progress, or movement into the future, and flourished in many formally different economic systems.

During the 1980s, but especially with the collapse of European Communism, and the birth of the so-called ‘Washington Consensus’, developmentalism became more strongly tied to international capitalism, and especially neoliberal capitalism. We can call this ‘neoliberal developmentalism’.

Neoliberalism 1

As I have argued elsewhere, neoliberalism is the set of policies whose holders argue in favour of liberty in free markets, but who (if having to make a choice), nearly always support established corporate plutocracy and appear to aim to destroy all political threats to that plutocracy.

Developmentalism and ecology

Developmentalism was built on fossil fuel use, and economic growth through cheap pollution and cheap ecological destruction. It also often involved large scale sacrifice of poorer people, who were generally considered backward and expendable in the quest for national greatness. Sometimes it is said that in the future succesful development will mean less poisoning, destruction and sacrifice, but the beautiful future may be continually postponed, as it was with communism.

Developmentalism was also often ruthlessly competative in relationship to other states and the pursuit of cheap resources. Developing countries often blame developed countries for their poverty, and this may well be historically true, as their resources were often taken elsewhere for little benefit to their Nation. Many developing countries also argue that they have the right to catch up with the developed world, through the methods the developed world used in the past. It is their turn to pollute and destroy. If this idea is criticised, then it usually becomes seen an attempt to keep them poverty ridden and to preserve the developed world’s power.

Developmentalism is related to neoliberal capitalism via the idea that you have to have continuing economic growth to have social progress, and that social progress is measured in consumerism and accumulated possessions. However, after a point neoliberalism is about the wealthy accumulating possessions, it does not mind other people loosing possessions if that is a consequence of its policy. Both the developing and developed world have developed hierarchies which tend to be plutocratic – development tends to benefit some more than others.

After the 1980s with the birth of neoliberal developmentalism, the idea of State supported welfare and development for the people was largely destroyed as developing States could not borrow money without ‘cutting back’ on what was decreed to be ‘non-essential’ spending. The amount of environmental destruction, pollution and greenhouse gas emissions also rocketed from that period onwards, despite the knowledge of the dangers of climate change and ecological destruction. The market became a governing trope of development, as it was of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism 2: The theory of Free Markets

In theory, ‘free markets’ are mechanisms of efficiently allocating resources and reducing all needs and values to price, or messages about price.

Theory does not always work, because large-scale markets are nearly always political systems rather than natural or impersonal systems.

Big or successful players in the market nearly always attempt to structure the market in their favour. Wealth grants access to all other forms of power such as violence, communicative, informational, legal, ethical, organisational, religious and so on. If there is no State, then successful players will found one to protect their interests and property. If there is a State they will collaborate with others to take it over to further protect their interests and property.

Everything that diminishes profit, especially profit for established power, is to be attacked as a corruption of the market and therefore immoral and to be suppressed. If people protest at not having food, or at being poisoned by industry, they are clearly immoral and not working hard enough. Political movements which oppose the plutocracy or its consequences may have their means of operation closed down, or find it difficult to communicate their ideas accurately through the corporate owned media. The market ends up being patterned by these politics.

For example, neoliberal free markets always seem to allow employers to team up to keep wages down, as that increases profit, and render Union action difficult as that impedes the market.

While these actions may not always have the desired consequences, the market, at best, becomes efficient in delivering profits, but only rarely in delivering other values. Thus people without money are unlikely to have food, or good food, delivered to them. Indeed those people may well be sacrificed to efficiently feed others who have both more than enough food and more disposable wealth, and hence who make more profits for the sellers.

Through these processes, there is an ongoing transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich, increased by the power relations of plutocracy.

In plutocracies, it is normal to think that the poor are clearly stupid or not worth while, rather than they have lost a political battle, or been unfortunate.

Neoliberalism and ecology

If it is profitable to transfer the costs of ecological destruction onto the less powerful, and less wealthy, public then it will be done as with other costs. The cost and consequences of destruction will not be factored into the process, and this will give greater profit.

Even, leaving the natural world in a state in which it can regenerate becomes counted as a cost. If it is cheaper to destroy and move on, most businesses will do this, especially the more mobile wealth becomes. For example, I was told yesterday that on some Pacific Islands, overseas fishing companies bought fishing rights to sea cucumbers (which are extremely valuable given the prices I saw in some shops). They took all the sea cucumbers they could, threw the smallest onto the beach to die, and moved on, leaving the area more or less empty. They had no ties to the place, or to the regeneration of local ecologies. The whole ecology of the islands could collapse as a result of this profit taking, but only the Islanders suffer in the short term.

Likewise spewing poison is good for business as it is cheaper than preventing it. Neoliberal governments will support or even encourage powerful pollutors, if they are established members of the plutocracy, as President Trump is demonstrating nearly every day. These pollutors and destroyers have wealth and can buy both government support and politicians in general. They can pay for campaigns and propaganda. They can promise easy well paid jobs in their industry, and those people who were politicians and are now in the industry demonstrate the benefits of this position and are persuasive. Within neoliberalism, with wealth as the prime marker of success, the destructive business people are also considered virtuous and superior people, so the destruction they produce must also be virtuous.

In this situation, objecting to cheap ecological destruction, or proposing ways of preventing such destruction becomes seen as an attack on the powerful and on morality of the system in general.

One of my friends who studies neoliberalism, seems to be coming to the view that neoliberalism’s first political success came about in the 1970s through opposing the idea of Limits to Growth, and supporting ideas of capitalist expansion through endless technological innovation and creativity. This movement assumes that (within capitalism) desired, or needed, technological innovation will always occur, and be implemented, with no dangerous unintended consequences. This seems unlikely to always be true, and to be primarily based in fantasy and wish-fulfillment. It was also probably more attractive to voters than voluntary austerity. It allowed the continuance of ‘development’.

If this is the case, then neoliberals (rather than Conservatives) have been implicated in anti-ecological thinking from the begining.

The UK and Germany actually have Conservative parts in the mainstream Right, and they seem relatively happy with moving from coal into renewables – so we are not talking about every form of capitalism being equally destructive.

In Australia, neoliberalism is reinforced by the learnt dependence of the official economy on resources exports – whether agricultural or mineral, both of which have tended to destroy or strain Australian ecologies. Most Australians think mining is much more important to the economy than it is, expecially after all the subsidies and royalty and tax evasions are factored in. This visions of success implies that destruction is probably acceptable. Australia is big after all, and most people never see the sites of destruction, even if they have large scale consequences.

These processes have lead to a power imbalance in Australia, in which the mining sector calls the shots, and boasts of its power to remove prime ministers. It not only creates loyalty, but also terror.

Renewables, less cheap pollution, less cheap destruction of ecologies, less poisoning, are threats to established ways of ‘developing’, and to be hindered, even if they are ‘economically’ preferable, or succesful in the market.

In this situation, it is perfectly natural that other forms of economy, or activities which could potentially restructure the economy and disrupt the plutocracy, should be stiffled by any means available. In this case, this includes increasing regulation on renewable energy, suggesting that more subsidies will be given to new fossil fuel power, and increasing penalties for protesting against those supporting, or profiting from, fossil fuels.

In Australia, Labor is rarely much better than the Coalition in this space, as the fuss after the last election has clearly shown. It is being said that they failed because they did not support coal or the aspirations of voters to succeed in plutocracy, and they vaguely supported unacceptable ‘progressive’ politics.

Neoliberalism as immortality project

This constant favouring of established wealth, leads to the situation in which people with wealth think they will be largely immune to problems if they maintain their wealth (and by implication shuffle the problems onto poorer people).

At the best it seems to be thought that wealthy people are so much smarter than everyone else, that they can deal with the problems, and this success with problems might trickle down to everyone else. Thus wealth has to be protected.

These factors make the plutocracy even more inward looking. Rather than observing the crumbling world, the wealthy are incentivised to start extracting more from their companies and the taxpayers, to keep them safe. They become even more prone to fantasy and to ignore realities.

Conclusion

Developmentalism and Neoliberalism constitute the major forms of policy dominating world governance, and visions of the future.

In the English speaking world neoliberalism dominates. We have more totalitarian neoliberals (Republicans, Liberals, Nationals) and more humanitarian neoliberals (Democrats, Labour etc).

In the rest of the world, developmentalism can occasionally dominate over neoliberalism (ie in China), but the idea of economic expansion and a degree of emulation of the supposed economic success of the ‘West’ remains a primary aim.

Developmentalism and Neoliberalism both establish and protect ecological destruction for wealth generation and are among the main social obstacles to a transition to renewables.