We seem to be facing a climate crisis already. We don’t have to wait for the future. This description is obviously not complete, and only deals with 2022.

Australia

There are severe floods in Eastern Australia again. The Climate Council calls them “one of the most extreme disasters in Australian history… causing tragic loss of life and submerging tens of thousands of homes and businesses.” They point to speed, severity and “rain bombs”. Yet this flooding occurred on the East Coast at the the same as Perth on the West Coast “smashed its previous record number of summer days at or over 40 C.” The Council recommends “Australia triple its efforts and aim to reduce its national emissions by 75% by 2030, and reach net zero by 2035.” The government is currently refusing to budge on its targets of 43% cuts by 2030 and net zero by 2050. This does not seem enough.

While the handling of the last floods may have been better than the previous floods, the country does not seem to be preparing for more events. Greg Mullins, former commissioner of Fire & Rescue NSW, Climate Council member, and founder of the Emergency Leaders for Climate Action states:

Australia lost a critical decade of preparation under a former federal government that repeatedly failed to heed the advice of scientists and experts… We are now in a position where we’re ill-equipped to get ahead of disasters and nowhere near where we should be to address the climate crisis.

Greg Mullins Australia is woefully unprepared for this climate reality of consecutive disasters. The Guardian 5 July 2022

Recently the NSW government scrapped orders to consider flood and fire risks before land zoning and building. The previous Federal Government delayed the release of a report into the condition of Australia’s environment until after the election. This has just been released. It appears to show a large number of newly threatened animals, with the country having one of the highest rates of species decline in the developed world, large scale forest clearance (not sure if this includes through the bushfires), a crisis in the Murray-Darling river system which is vital for agriculture and inland life, repeated bleachings of the Great Barrier Reef, increased ocean acidity, sea level rise affecting low-lying areas, such as the Kakadu wetlands, loss of soil carbon, and so on. The new Minister for the Environment stated that “The Australian Land Conservation Alliance estimates that we need to spend over $1 billion a year to restore and prevent further landscape degradation”.

The president of the Australian Academy of Science, Prof Chennupati Jagadish, said the report was sobering reading and the outlook for the environment was grim, with critical thresholds in many natural systems likely to be exceeded as global heating continued

Adam Morton and Graham Readfearn State of the environment: shocking report shows how Australia’s land and wildlife are being gradually destroyed The Guardian Tue 19 Jul 2022 03.30 AEST

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology states:

Australia has warmed on average by 1.44 ± 0.24 °C since national records began in 1910, with most warming occurring since 1950 and every decade since then being warmer than the ones before. Australia’s warmest year on record was 2019, and the seven years from 2013 to 2019 all rank in the nine warmest years.

State of the Climate 2020

It appears that Australia is already close to exceeding the 1.5C increase, that was an acceptable target.

Staying under 1.5C, or even setting a good example, is unlikely, as Australian emissions have recently increased in most areas of the economy, with the exception of electricity.

- Increased transport emissions (up 4.0%; 3.5 Mt CO₂-e) reflecting a continuing recovery from the impacts of COVID restrictions on movement

- Increased emissions from stationary energy (excluding electricity) (up 3.3%; 3.3 Mt CO₂-e) driven primarily by an increase in fuel combustion in the manufacturing sector

- Increased emissions from agriculture (up 4.2%; 3.1 Mt CO₂-e) due to the continuing recovery from drought

- Increased fugitive emissions (up 1.8%; 0.9 Mt CO₂-e), resulting from increased venting and flaring in oil and gas.

The latest list on the Department of Industry Science and Resources (p.8) Lists 69 new coal projects and 45 new gas and oil projects in various stages of approval. This could change with the new government, but it seems unlikely. Rupert Murdoch’s The Australian reports the new Prime Minister as saying new coal and gas projects could proceed if they stacked up financially and passed environmental approvals and “Policies that would just result in a replacement of Australian resources with resources that are less clean from other countries would lead to an increase in global emissions, not a decrease” [Albanese: coal ban won’t cut emissions, The Australian, 21 July 2022: 4.]. This was a conventional line repeated by the Minster for Environment: “Other countries that are burning Australian coal are responsible for reducing the pollution when they’re burning that Australian coal. That is how the global accounting for carbon pollution reduction works.” It also appears that Australian based Fossil Fuel companies have also been announcing massive profit increases. For example, Woodside announced a 44% increase in revenue. Santos an 85% increase despite only increasing production by 9%. Whitehaven Coal announced that it received a “record” average price for coal over the second quarter in 2022, over 5 times what it charged the previous year.

The weather conditions elsewhere are also ‘difficult’.

UK

There is the current heat wave in the UK, with record temperatures, melting runways, warnings for people not to commute, trains cancelled and so on. The UK Met Office issued its first-ever Level 4 “extreme heat” warning indicating that even the fit and healthy could fall ill or die, not just the high-risk and vulnerable groups. The hottest temperature ever recorded in the UK of 40.2C at Heathrow. This broke the previous record of 38.7C set in 2019.

Dr Eunice Lo, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol Cabot Institute for the Environment, said: “The climate has warmed since 1976 significantly. We have a record going back to 1884 and the top 10 hottest years have all occurred since 2002…. This hasn’t happened before; it is unprecedented…. By definition these are new extremes.”

Helena Horton UK is no longer a cold country and must adapt to heat, say climate scientists. The Guardian 18 July 2022

The UK Met said:

The chances of seeing 40°C days in the UK could be as much as 10 times more likely in the current climate than under a natural climate unaffected by human influence.

UK prepares for historic hot spell. Met Office News. 15 Jul 2022.

To add to the Strangeness. The normal source of the River Themes has dried up, and the river now starts 5 miles downstream from that point. There is a drought.

Apparently some UK climate scientists said that they had not expected these kinds of temperatures in the UK this early. Yet the simultaneous Conservative Party leadership ballot, has had candidates accused of ignoring climate change. The two finalists Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss have both expressed caution. Sunak said “If we go too hard and too fast” toward net zero “then we will lose people,” and Truss said she wanted to “find better ways to deliver net zero” that won’t “harm people and businesses” [1]. Truss has generally voted against climate measures.

EU

Fires are burning in France, Spain, Portugal, Croatia and Hungary. At least 12 thousand of people have been evacuated from the Gironde in south-western France. [Later reports suggest 37,000] According to the French weather channel La Chaîne Météo 108 absolute temperature records were set. Some Nuclear Reactors where turned down as the cooling water was too hot. In Spain temperatures reached 45C and 3,000 people were evacuated from the town of Mijas due to fires. The arrival of 30C temperatures in Spain has “advanced between 20 and 40 days on average in 71 years, according to a climatological study by” the State Meteorological Agency (Aemet) “the climate of Spain no longer It is as we knew it: it has become more extreme” the four seasons in Spain will end up being two: summer and almost summer (Via Google Translate). Fires have also broken out near Athens [more] fanned by gales and heat. A hospital and the National Observatory of Athens were evacuated, and homes were burnt down.

The French Prime Minister warned that France is facing its “most severe drought” on record. “The exceptional drought we are currently experiencing is depriving many municipalities of water and is a tragedy for our farmers, our ecosystems and biodiversity.” Apparently more than 100 municipalities were not able to provide drinking water to the tap and had to be supplied by truck. Portugal having recorded its highest July temperature is nearly completely in severe or extreme drought. In Italy, the Po is 2 metres lower than normal, and increased salinity is threatening rice and shellfish production. Further reports suggest that the Rhine river is 7 cm off being unsuitable for river traffic and this will affect trade all through the continent, and add to the stress coming from the heat, the energy shortage, and the war in Ukraine.

Andrea Toreti of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre [sais] “There were no other events in the past 500 [years] similar to the drought of 2018. But this year, I think, is worse.”

Henley, J. Europe’s rivers run dry as scientists warn drought could be worst in 500 years. The Guardian, 14 August 2022

Only 3% of homes in Germany and the UK have air-conditioning, 5% of residential homes in France, 7% in Italy. The heat waves suggest that there will also be a wave of power consumption as people start to install cooling in their homes. Radhika Khosla, associate professor at the Smith School at the University of Oxford, made the obvious point about needing air conditioning in a heated world:

“The global community must commit to sustainable cooling, or risk locking the world into a deadly feedback loop, where demand for cooling energy drives further greenhouse gas emissions and results in even more global warming.”

Fiona Harvey, Ashifa Kassam, Nina Lakhani, and Amrit Dhillon Burning planet: why are the world’s heatwaves getting more intense? The Guardian 19 June 2022

There is also likely to be struggles over available energy in Europe over the winter. Frans Timmermans the vice-president of the European Commission has warned the EU could descend into serious strife if there wasn’t enough energy for heating in winter, and “If we were just to say no more coal right now, we wouldn’t be very convincing in some of our member states and we would contribute to tensions within our society getting even higher.” So “can we make further commitments on reducing our emissions given the situation?” The answer he was implying was ‘no’.

The heat and fires are likely to affect farming and food availability. Mustard for example is short in France because of excessive heat in Canada where much of their mustard seed is grown. An estimated 15 to 35% of the wheat crop in states close to Delhi such as Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh – what is known as India’s “wheat bowl” – has been damaged and the government banned wheat exports.

USA

In the US

Nearly 90 large fires and complexes have burned 3,100,941 acres in 12 states. Six new large fires were reported, two in Alaska and one in Alabama, Idaho, Montana and Oklahoma. More than 6,600 wildland firefighters and support personnel are assigned to incidents across the country

National Interagency Fire Center National Fire News 18 July 2022 [this link is likely to be lost due to updates]

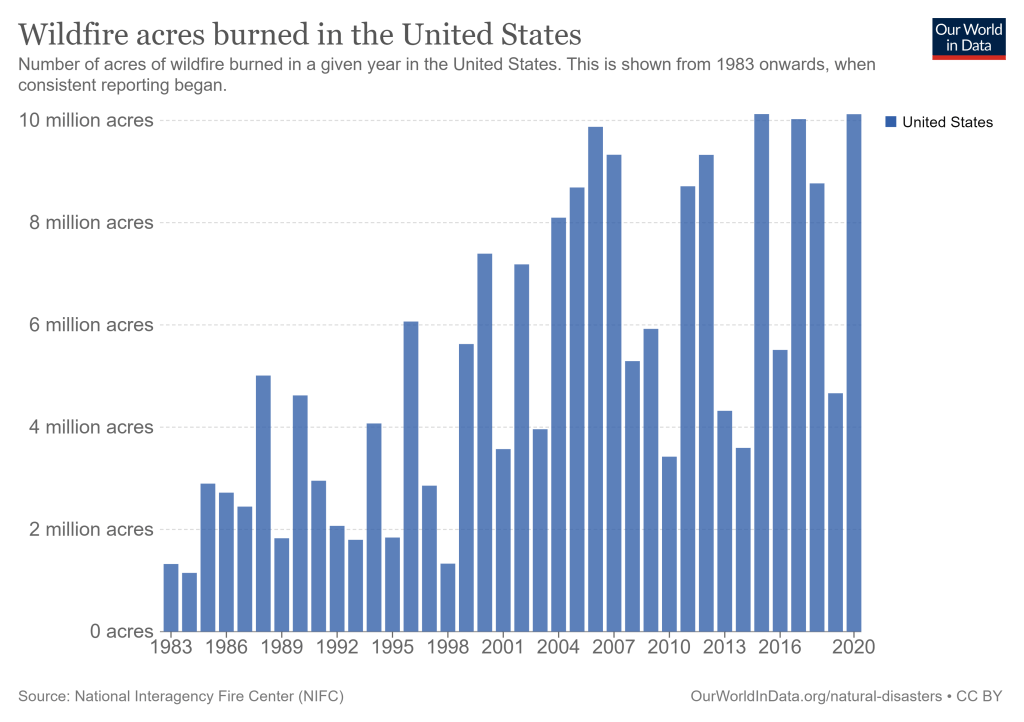

The amount of the USA being burnt seems to be increasing… By early July the Alaskan fires had burnt over 2 million acres, more than twice the size of a typical Alaska fire season.

the weather factors – the warm spring, low snowpack and unusual thunderstorm activity – combined with multidecade warming that has allowed vegetation to grow in Southwest Alaska, together fuel an active fire season…. [The fires] burn hotter and burn deeper into the ground, so rather than just scorching the trees and burning the undergrowth, they’re consuming everything, and you’re left with this moonscape of ash

Rick Thoman Alaska on fire: Thousands of lightning strikes and a warming climate put Alaska on pace for another historic fire season. The Conversation 5 July 2022

In California there are large fires almost every year nowadays. The ‘Oak fire’ in Mariposa county has led to 6000 people being evacuated.

On Saturday, the Oak fire sent up a pyrocumulus cloud so large it could be seen from space…. Kim Zagaris, an adviser for the Western Fire Chiefs association, told the LA Times: “When you get a pyrocumulus column, it can pick up a pretty good-sized branch and actually draw it aloft into the column and in some cases drop it a mile or two miles down the head of the fire, which starts additional spot fires.”….. Felix Castro, a meteorologist with the US National Weather Service, said the region had experienced 13 consecutive days of triple-digit heat with relative humidity of 8% or 9%. Vegetation had reached near-record dryness, he said, in what scientists estimate to be the most arid 22-year period in at least 1,200 years.

Gabrielle Canon Edward Helmore, California Oak fire remains uncontained as Al Gore warns ‘civilization at stake’. The Guardian 25 July 2022

There were unexpected heat waves in Texas and Arizona with daily temperature records, and record overnight temperatures. Some cities opened cooling centres for people without air conditioning. Texas warned people to cut electricity use or face blackouts. “Extreme heat is America’s leading weather-related killer, and Phoenix in Maricopa county [Arizona] is the country’s hottest and deadliest city.”

Water shortage’s are common in Western USA, due to a long term drought. In Mid August, the US Department of the Interior declared the first-ever tier 2 water shortage for the Colorado River, so Arizona, Nevada and Mexico have to reduce their water usage even more from 1 January next year. Not only is the ecology of the river basin threatened, but humans will face disrupted water supplies and diminished hydro electric capacity. This has already increased tensions between the different states.

The Democrats have not been particularly successful getting climate measures passed, and Biden has proposed new offshore oil drilling off Alaska and in the Mexican Gulf.

‘Sub-continent’: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh

Earlier in the year there were heat waves in Pakistan and India showing the highest temperatures on record. According to the Meteorological Department Delhi has recorded temperatures of 42C (and above) on 25 days since summer began. Temperatures of about 50C were seen in May, while India had 71% less rain than normal in March and there was 62% less rainfall in Pakistan. People from the World Meteorological Association wrote:

The 2022 heatwave is estimated to have led to at least 90 deaths across India and Pakistan, and to have triggered an extreme Glacial Lake Outburst Flood in northern Pakistan and forest fires in India. The heat reduced India’s wheat crop yields, causing the government to reverse an earlier plan to supplement the global wheat supply that has been impacted by the war in Ukraine. In India, a shortage of coal led to power outages that limited access to cooling, compounding health impacts and forcing millions of people to use coping mechanisms such as limiting activity to the early morning and evening… Because of climate change, the probability of an event such as that in 2022 has increased by a factor of about 30.

Zachariah et al Climate Change made devastating early heat in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely

Bangladesh has been having the worst floods in Sylhet in a century. Thousands of people are displaced, towns have been washed away. According to the UN, an estimated 7.2 million people across seven districts have been affected. Hospitals are inaccessible due to flooding. Over half of the regions medical clinics are underwater. “An estimated 60,000 women are pregnant in the affected region, with more than 6,500 births expected to take place in July”, and the lack of medical resources also means that waterborne diseases are likely to sweep through the population.

India has apparently used the heat wave and failing power sources to reduce environmental compliance rules for coal mines, such as holding public consultations before mines operate at greater capacity. The government plans to increase coal production to 1.2 billion tonnes, an increase of over 400m tonnes, over the next two years

Latin America

Conditions where not good in Latin America early this year

In mid-January, the southern tip of South America suffered its worst heat wave in years. In Argentina, temperatures in more than 50 cities rose above 40°C, more than 10°C warmer than the typical average temperature in cities such as Buenos Aires. The scorching heat sparked wildfires, worsened a drought, hurt agriculture, and temporarily collapsed Buenos Aires’s electrical power supply.

Rodrigo Perez Ortega Extreme temperatures in major Latin American cities could be linked to nearly 1 million deaths. Science 28 June 2022

China

In China, at least 86 Chinese cities in eastern and southern parts of the country had issued heat alerts. in the city of Nanjing, officials opened air-raid shelters for locals to escape the heat. Reports from earlier in the year suggest that Premier Li Keqiang announced a goal of 300 million tons of new coal production in 2022, in addition to the 220 million tons added last year.

Africa

Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia are facing lack of rainfall and a drought emergency [1], [2]

The Poles

Temperatures at Vostok station relatively near the South Pole were 15C hotter than the previous all-time record. At the North Pole temperatures were 3C higher than average. Science Daily reported research which showed that “the Arctic is heating up more than four times faster than the rate of global warming.” (See also here) The ice melts reveal more ‘dark sea’ which will absorb more heat and, in a positive feedback loop, lead to higher temperatures and more ice melts

State of the global climate

The World Meteorological Association State of the Global Climate 2021 report’s ley points include:

- The global mean temperature in 2021 was around 1.11 ± 0.13 °C above the 1850–1900 pre-industrial average…. The most recent seven years, 2015 to 2021, were the seven warmest years on record.

- Global mean sea level reached a new record high in 2021, rising an average of 4.5 mm per year over the period 2013–2021.

- Greenland experienced an exceptional mid-August melt event and the first-ever recorded rainfall at Summit Station, the highest point on the Greenland ice sheet at an altitude of 3,216 m.

- Exceptional heatwaves broke records across western North America and the Mediterranean. Death Valley, California reached 54.4 °C on 9 July, equalling a similar 2020 value as the highest recorded in the world since at least the 1930s, and Syracuse in Sicily reached 48.8 °C.

- Hurricane Ida was the most significant of the North Atlantic season, making landfall in Louisiana on 29 August, equalling the strongest landfall on record for the state, with economic losses in the United States estimated at US$ 75 billion.

- Deadly and costly flooding induced economic losses of US$ 17.7 billion in Henan province of China, and Western Europe experienced some of its most severe flooding on record in mid-July. This event was associated with economic losses in Germany exceeding US$ 20 billion.

- Drought affected many parts of the world, including areas in Canada, United States, Islamic Republic of Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey and Turkmenistan. In Canada, severe drought led to forecast wheat and canola crop production levels being 35%–40% below 2020 levels, while in the United States, the level of Lake Mead on the Colorado River fell in July to 47 m below full supply level, the lowest level on record.

- Hydro-meteorological hazards continued to contribute to internal displacement. The countries with the highest numbers of displacements recorded as of October 2021 were China (more than 1.4 million), Viet Nam (more than 664 000) and the Philippines (more than 600 000).

These weather patterns seem entirely consistent with the idea that climate change had arrived and that weather is getting more chaotic and disruptive.

Cost of Damage?

It is clearly not possible, as yet, to estimate the damage for 2022, but Munich RE, (a provider of reinsurance, primary insurance and insurance-related risk solutions) has estimated the costs for the ‘milder’ year of 2021:

- In 2021, natural disasters caused overall losses of US$ 280bn, of which roughly US$ 120bn were insured

- Alongside 2005 and 2011, the year 2021 proved to be the second-costliest ever for the insurance sector (record year 2017: US$ 146bn, inflation-adjusted) – overall losses from natural disasters were the fourth-highest to date (record year 2011: US$ 355bn)

- Hurricane Ida was the year’s costliest natural disaster, with overall losses of US$ 65bn (insured losses of US$ 36bn)

- In Europe, flash floods after extreme rainfall caused losses of US$ 54bn (€46bn) – the costliest natural disaster on record in Germany

- Many of the weather catastrophes fit in with the expected consequences of climate change, making greater loss preparedness and climate protection a matter of urgency….

- The USA accounted for a very high share of natural disaster losses in 2021 (roughly US$ 145bn), of which some US$ 85bn were insured

Five Final Opinions

Carbon Brief, is an activist organisation, so you may want to ignore it….

We found more than 400 new mine proposals that could produce 2,277m tonnes per annum (Mtpa), of which 614Mtpa are already being developed. The plans are heavily concentrated in a few coal-rich regions across China, Australia, India and Russia.

If they all went ahead, the new mines could supply as much as 30% of existing global coal production – or the combined output of India, Australia, Indonesia and the US.

Yet last month, the International Energy Agency said no new coal mines – nor extensions of existing mines – were “required” in its pathway to 1.5C. A UNEP report last year said coal output should fall 11% each year to 2030, under the same target.

Plans to massively boost coal production are, therefore, incompatible with the 1.5C limit. Alternatively, if global climate goals are to be met, the estimated $91bn of investment in the proposed mines could be left stranded.

Guest post: Hundreds of planned coal mines ‘incompatible with 1.5C target’ Carbon Tracker 10 June 2021

The UN Secretary General to the G20:

The climate crisis is our number one emergency.

The battle to keep the 1.5-degree goal alive will be won or lost by 2030….

But current national climate pledges would result in an increase in emissions of 14 percent by 2030.

This is collective suicide.

We need a renewable energy revolution. Ending the global addiction to fossil fuels is priority number one.

No new coal plants.

No expansion in oil and gas exploration….

Emerging economies must have access to the resources and technology they need.

Wealthier countries must finally make good on the $100 billion climate finance commitment to developing countries, starting this year.

We also need a radical boost for adaptation and early warning systems.

Secretary-General’s video message to the G20 Foreign Ministers: “Strengthening Multilateralism” 8 July

Later he said:

Eight months ago we left COP26 with 1.5 on life support.

Since then, its pulse has weakened further.

Greenhouse gas concentrations, sea level rise and ocean heat have broken new records.

Half of humanity is in the danger zone from floods, droughts, extreme storms and wildfires.

No nation is immune.

Yet we continue to feed our fossil fuel addiction.

What troubles me most is that, in facing this global crisis, we are failing to work together as a multilateral community.

Nations continue to play the blame game instead of taking responsibility for our collective future.

Secretary-General’s video message to the Petersberg Dialogue 18 July 2022

The Chair of the IPCC, said at the launch of the Working Group II report.

The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a grave and mounting threat to human wellbeing and the health of the planet. Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future.

We are not on track to achieve a climate-resilient sustainable world.

This report is a dire warning about the consequences of inaction.

Opening remarks by the IPCC Chair at the IPCC-SBSTA Special Event on the Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report Monday, 6 June 2022

Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy in the US and professor at Texas Tech University says:

We cannot adapt our way out of the climate crisis…. If we continue with business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions, there is no adaptation that is possible. You just can’t…. Our infrastructure, worth trillions of dollars, built over decades, was built for a planet that no longer exists… Human civilisation is based on the assumption of a stable climate…. But we are moving far beyond the stable range. We will not have anything left that we value, if we do not address the climate crisis

Fiona Harvey We cannot adapt our way out of climate crisis, warns leading scientist. The Guardian 1 June 2022

Concluding comments

Let’s be clear this is only the beginnings of actual observable climate change. Not the end. These events are happening within what was considered the ‘safe range’ of a global average under 1.5C rise. We are continuing to make the situation worse, and there is always a delay….

The need to cut GHG gas emissions and transition to renewable energy quickly appears to begin the only way that present day large scale civilisations can survive. Hence you would think transition might be an urgent priority – although it still seems to be an urgent priority to have more coal and gas supplies.

However, we have several problems, the world is distracted by the ongoing mutating pandemic, the war in Ukraine (and there is no necessity that the war remains contained), is taking money away from climate mitigation and adaptation, and causing shortages of gas which is causing countries to open old coal plants, increase emissions, while also causing food shortages. Tackling inflation by putting up interest rates is likely to cause defaults not only on the housing market, but to countries and companies who are indebted and only just managing, which will likely cause an economic crisis, which will hinder ecological restoration and ambitious plans for energy transformation. The chaotic weather is also likely to disrupt travel and economic production and increase demand for electricity for air-conditioning and cooling, adding to the problems of energy, productive capacity and available money.