Capitalism is not the same everywhere, but in the English speaking world it has a number of stages, which might be described as: Theft and Conquest; Consolidation and Worker’s Rise; People’s Capitalism; Plutocracy and; Crisis and Fascism. All the stages can overlap, and they may not always appear in sequence.

People’s capitalism’ is probably one of the better forms of social life. Certainly it is better than militarism, theocracy, complete state control over everything. However, pro-corporate capitalist writers tend to move from this relative fact to insisting that capitalism is without significant flaws in every stage, and thus should be left alone.

If left alone, then capitalism will nearly always become rule of the rich, or plutocracy. The theory of this is easy to understand. In capitalism, wealthy people are seen as virtuous and have status. They are largely admired for their success. Wealthy people also have much larger amounts of disposable wealth than ‘ordinary people’. Wealthy people can easily team up and promote legislation which supports what they see as their interests, without much opposition. They can buy politicians. They can buy laws and lawyers. They can buy “think tanks”. They control information through owning and controlling the media, large and small. Smallness of media is no guarantee of accuracy, or liberty from the control of wealth.

In capitalism, there is no source of power which cannot be bought from violence to religion. Consequently, wealth is the source of nearly all power, and of all differences in power. Wealth is used to support the wealthy and hinder anyone else from challenging them. This is quite natural. This does not mean there are no factions amongst the wealthy; some, for example, may have more sense of obligation to those ‘beneath them’ than others, but because the wealthy control the sources of information, these differences may be hard to detect accurately.

It seems fairly obvious, that regulation favouring established wealth will not always work out well for everyone. It will have unintended and harmful consequences. It can stop the best part of capitalism, namely the ability of new success to tear down the old wealth and power establishment, and set up new businesses, new technologies and new business models.

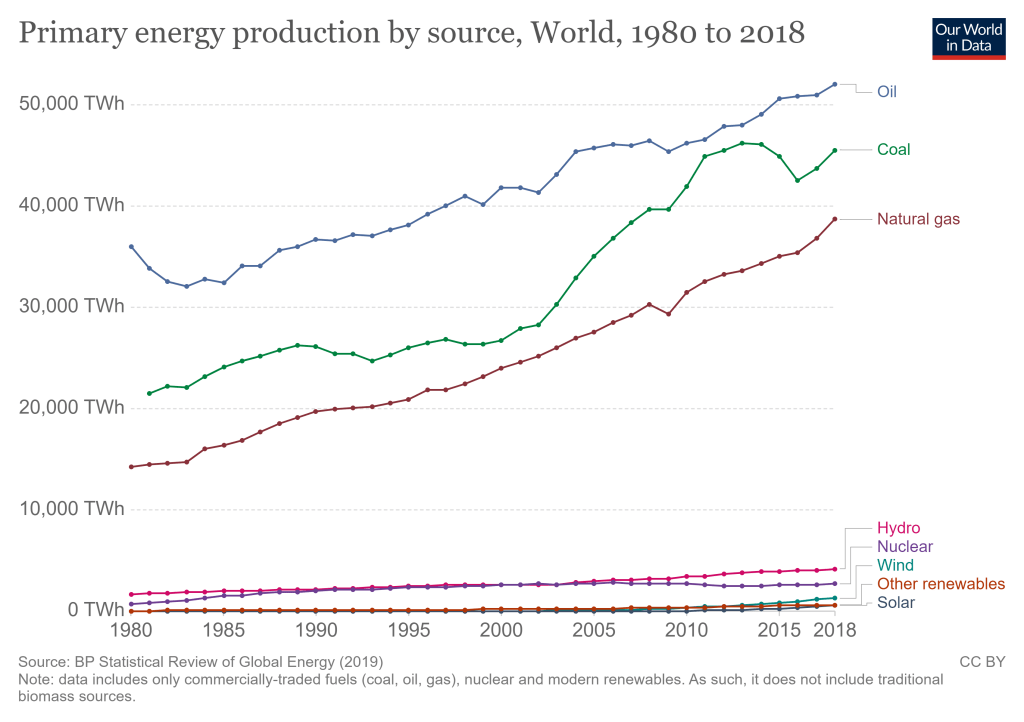

In plutocratic capitalism, owners, high level executives and directors tend to know each other, and support each other, and engineer the distribution of wealth, so having contacts rather than talent is rewarded. Established companies tend to receive heaps of taxpayers’ money during a crisis to bail them out and keep them running. They can also receive more favourable regulations, or lessening of regulation. That appears to be what is happening in the Covid crisis – especially with fossil fuel companies. In the financial crisis of 2007-8 there was plenty of money to bail out financial corporations, but very little to bail out ordinary people who had taken fraudulent, or entrapping, loans. Wealthy capitalists were protected from the consequences of their actions – and some parties claimed those companies receiving bailouts should not have to pay any of the gifted taxpayers’ money back.

In this plutocratic stage, it often happens that new industries which challenge established ones are regulated out of existence by established wealth, or find it much harder to operate than they should. Sometimes, as with large stores, established business can effectively use their market power to stop small business from being economic. Hence the crisis in small business today.

If there is a real crisis which will not fix itself profitably (such as ecological exhaustion, serious pandemic, decline of an important resource, massive inflation, stagflation etc), and the State is supposedly democratic, then many of the established wealthy groups tend to abandon any restraint in attempting to preserve their power and wealth.

They may attempt to split ordinary people by encouraging hatreds amongst the population, scapegoating minorities, misdirecting people’s anger against the wealthy into support for the wealthy, encouraging police violence and so on. They may find a nice demagogue – that is, a highly persuasive and unprincipled person – who will say anything to take lead of the State – with the violence against dissent getting more and more intense as this leader solidifies their power.

This is the beginning of fascism. Fascist processes are encouraged as an attempt to provide stability for a form capitalism in crisis. While the fascists build on the power of wealth at the beginning of their moves, they slowly take it over, usually through violence from the party and its militias. Some of the established wealthy manage to accommodate to the fascists. However, along with the scapegoats, some of the established wealthy people get eliminated, or realise they have stuffed it badly for themselves. But most of the wealthy were never in favour of democracy anyway, as it disrupts their power and their freedom, and they prefer the apparent discipline of fascism, the suppression of unpleasant opposition and the appearance of a solution to their problems, which should not cost them anything.

So there is a tendency for capitalism to end in violence when it hits a crisis, especially a crisis that capitalism generates itself – such as the increasing ecological crisis.

Violence is no stranger to capitalism. Some people argue that capitalism always grows out of violence and theft. For example, European and American capitalism, grew out of violent conquest, slavery, murder, dispossession of people from their lands (not only in America, Australia, India and Africa, but in the UK as well), the destruction of land, stripping wealth and resources from countries, the imposition of drug addiction in China by gunboats, and so on. It was an easy form of accumulation which provided some people with capital which they could use to start up business.

This violent theft gets legitimated, and turned into property by the plunderer’s influence in the State which made laws justifying the theft, or because this wealth collection is part of a State project to begin with. Sometimes State armies are used against people who protest against any of this. This period was not pleasant for those people who suffered and died to make capitalism successful.

Capitalism only seems peaceful because, over generations, people forget the violence, and people are not reminded by the capitalist owned media about the violence in their history, or the violence that is going on now. You have to do that research for yourselves. The point is that the capitalist wealthy are already used to violence, or ignoring their violence, and the violence of fascism can seem necessary if it seems to be protecting them from risk.

If the wealthy go the fascist way, then eventually the fascist leader, they have promoted or supported, becomes dictator and leads the country to war to gain new resources, to build the people’s loyalty and because the fascist rulers enjoy violence. That usually results in collapse, as the country extends beyond its military capacity, and generates more and more opposition from other powers.

So the major cycle goes: capitalism is born in plunder and dispossession, leading to massive wealth inequalities, which leads to plutocracy which aims to preserve the power and wealth inequalities. Plutocracy plus crisis leads to fascism, which usually leads to war and suffering for most people.

This cycle, can in theory be interrupted, by ‘people’s capitalism’, or to be more dramatic ‘socialist capitalism’ as found in the Nordic States or in the UK after the Second World war. People’s capitalism seems relatively precarious. It arises through political action from ordinary people, not through economic necessity, and is vulnerable if the wealthy decide that they have nothing to fear from the people.

Historically, it began to arise towards the end of the 19th Century, when workers began to organise and demanded better wages and conditions. Capitalists feared communist revolution – the “spectre haunting Europe”. As a result, a kind of truce occurred in the capitalist west in which wealth was somewhat shared, people got educated, the State became mildly helpful to everyone and protected people (to some extent) from misfortune. Ordinary people began to prosper a little, and social mobility increased.

The more that people share the wealth being produced, and the more governments act to help people to get opportunity and advancement, hinder the powers of corporations to exploit or poison people, set up competition to capitalist activities, and break up capitalist monopolies (or duopolies), then the longer capitalism will work and the people flourish.

This movement heightened after World War II and between the 1950s to 1970s capitalism was pretty good for most people, and it seemed to be steadily improving.

However with the collapse of the threat of revolution with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the wind down of worker organisation, plutocracy has been growing again. This plutocracy grew along with intense talk of free markets, attempts to destroy unions, and largely successful attempts to stop people from having much control over corporate activity as it interfered with the ‘free market’. Neoliberals successfully promoted the idea that the economy was the most important thing in life.

Given the many crises we face, the corporate world now seems to be heading for fascism again to preserve its wealth and power in the face of those crises. The choice is pretty clear. If, at this moment, a party supports action against the ecological crisis then it is probably not fascist. If it supports action which opposes ecological action or allows pollution to get worse, it probably is supporting the current set up at all cost, and will ultimately become fascist if it is not already.

It should not be a surprise that most pro-capitalist analyses of capitalism, such a neoclassical economics, or Austrian economics, tend to ‘forget’ the importance of accumulating differences in wealth and success, how this ends ‘free markets’, and the class politics involved in attempting to maintain, or lessen, that difference. Both of these factors are essential to understanding how the system works in the long term.