Previously I have suggested that there is a common form of skepticism, which is not a real skepticism as it is directed. It is only skeptical of particular positions, and because of this tends to be politically active, or result from politics. It is the kind of skepticism that is skeptical of the motives of climate scientists, but unskeptical of the motives of climate denialists. It appears to be motivated, although it is not always the user who is motivated; they main gain their motivation through the one sided skepticism of their exemplars. Sometimes the direction comes from what is socially accepted as common sense, and is thus not challenged, or from common defense against the possibilities of forthcoming pain. There is also a kind of cache in information society about being skeptical, even while you are apparently believing rubbish – directed skepticism is particularly useful in that situation.

In this piece I consider a skeptical argument, based on one proposed to me by a very smart guy, and attempt to show this skepticism is directed rather than general.

The post, also touches on interconnection and complexity; we can be skeptical of these views, but we should also be skeptical of views which do not take interconnection and complexity seriously. In a pandemic, everyone’s actions have the possibility of affecting many others, and many others through those others. An individual act has the potential to move outwards through society – a ‘humorous’ cough in someone’s face could spread the disease, even if the cougher does not feel sick.

1) I am skeptical that the current restrictions placed on the people of the world, which amount to a draconian dictatorship, are connected to the virus.

Response: I’m skeptical the restrictions amount to a draconian dictatorship, or that they have a specific aim other than lowering the disease.

Physical separation is the standard and historic mode of dealing with contagious diseases which are lethal. We try and keep healthy people away from sources of infection. We try and stop infected people passing on their infection. There is little that seems overtly odd about this. Diseases spread through social interconnection. We might be skeptical as to whether the proposed “social distancing” will work by itself, or that the consequences of this distancing are entirely predictable, but there seems little reason to think the rather diverse set of distancing regulations we observe are not primarily connected to a response to the virus. With the internet they certainly do not keep people socially isolated.

The death rate and the infection rate in Australia is way, way less than in the US, and the main difference is the speed and effectiveness with which the governments imposed distancing. So the better the isolation, it seems the better the result – at the moment.

As a rather trivial remark, I don’t know of people being executed for breaking restrictions which was the hallmark of Draco’s laws… And there is nothing I’ve seen to indicate the laws are coherent across the world. I’m skeptical that the relatively mild lock-downs in Europe, the US or Australia, are an indication of harsh dictatorship – certainly without considerably more evidence than is being offered. At the moment, these allegations seem over-emphasised.

It is true, that rather than making attempts to make distancing compulsory, it might be nice if we could persuade people to volunteer to cooperate in distancing, or for employers to decide everyone could work at home, out of the goodness of their heart, but I’m skeptical this would always happen. We appear to live in a society which does not always recognise a general good. However, there is always the factor of time. It appears that reaction to a pandemic must be reasonably quick to have effects.

However, the plausibility of distancing, does not mean we may not be able to find better solutions.

I am also skeptical that all those opposed to lock-down are necessarily proponents of freedom and liberty. Indeed, the organisations which seem devoted to diminishing human freedom and cultivating subservience to the corporate sector or State, such as US Republicans, British Tories, Australian Coalition, Putin, Modi, Bolsonaro, etc are generally trying to pretend there is no, to little, problem.

I’m skeptical of the idea that they do not anticipate benefit from encouraging skepticism about the disease and getting people to risk their lives on their behalf.

On the other hand, I don’t see who is benefiting politically from quarantine, other than ordinary people – if they get income support. The only underhand things that seem to be happening while the disease provides distraction, are the channeling of recovery money to wealthy people and established companies, and lessening restrictions on pollution and environmental destruction. That seems like business as usual, and apparently illustrates the idea that capitalist development requires ecological destruction.

2) Given that Governments are not dealing with severe problems, I’m skeptical that this is a serious problem.

Response: I’m skeptical of the idea that because governments do not deal with some major problems, they may never attempt to deal with major problems.

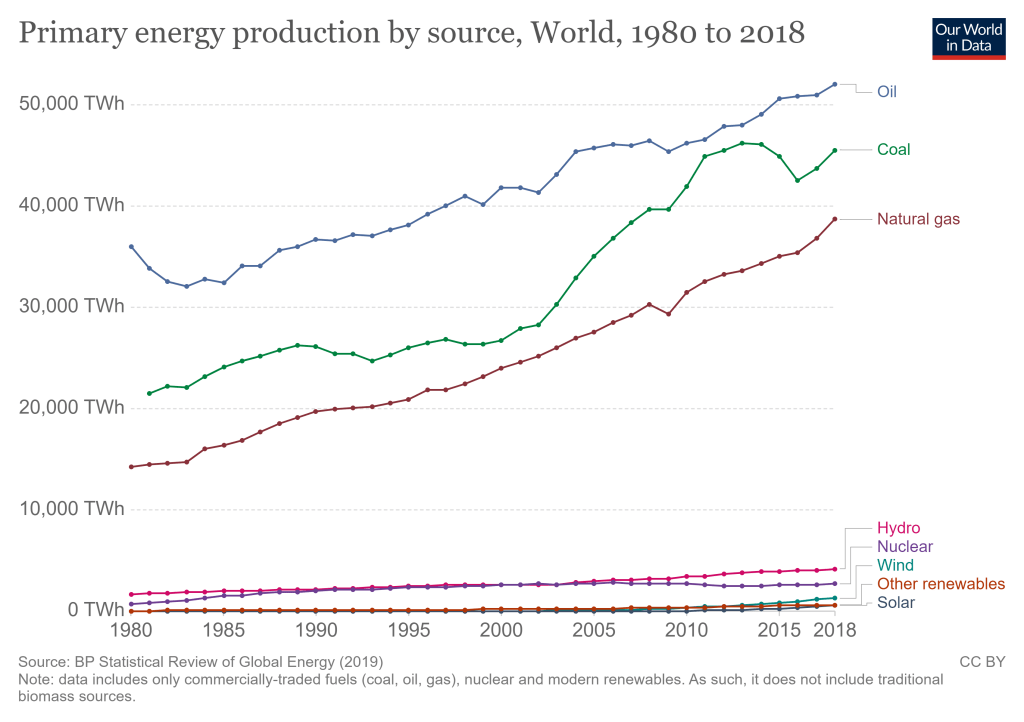

It does seem correct that governments are not dealing with severe problems such as climate change, ecological destruction, rising wealth inequality, or the growing dominance of the corporate sector etc. but it could be that the dominant classes think they can make money out of ecological destruction with no personal risk, while COVID-19 is potentially dangerous to them.

However the more COVID-19 effects the economy, and the more it does start to affect their wealth, then the more they appear to want to do nothing about it. They are also able to practice self-isolation to keep safe.

In this situation, I am skeptical that we will continue to deal with this problem. I suspect we will revert to the ways that we deal with other severe problems, by pretending they are not real or significant.

3) I am skeptical of anything in the mainstream media. The mainstream media is obviously fully behind the agenda of control. I place a question mark over everything I encounter in the media on both sides. I don’t trust any of the world’s government’s left or right.

Response: I’m skeptical of the idea the media speaks with one voice, or that what is reported by some media is always absolutely wrong.

If you don’t trust any of the world’s governments, then you should also be skeptical of the reasons given by those governments who oppose lock-down as well.

While saying “the media is arguing in favour of something” is always supposed to indicate that what those various sources are arguing for is suspect, it is possible they argue for things because they believe them to be true or strategically beneficial, even if they are not.

I am skeptical that because youtube channels, Q-Anon, or other mainstream news like Brietbart, may have ‘odd’ or different news, they are necessarily correct, or a voice of truth.

It also seems to be the case that not all media is fully behind lock-down, even if they were behind control. The Murdoch Empire for example, often argues in favor of whatever Trump’s position is at the moment, and generally of the disease being trivial. It is as mainstream and corporate as it gets.

I’m skeptical that people know about the world independently of media. Where else do they get their ideas about the wider world from? I am skeptical of the degrees of co-ordination required to fake a disease, across the world. I am skeptical of my own knowledge that would enable me to say the media is always wrong, even if it was uniform, which it isn’t.

There is lots of conflicting information but none of it, that I have seen, is able to imply that there is any logical ulterior motive in the way lock-down has been applied.

Lock-down may not be effective. That is a different question.

4) Even going by the highest statistics, the death rate is very small. I’m skeptical about this disease being harmful.

Response: I’m skeptical we know much about the disease as it is relatively new, and organisms and their interactions, and spread are complex. It may be deadly and destructive. It may not. It may be destructive enough. We will find out eventually.

Going on previous experience we can probably assume that humans will not have great defenses against a new disease, if this is a new disease.

My understanding is that the current medical understanding states that COVID-19 is more contagious than flu, and can be contagious before people exhibit notable symptoms. It is therefore likely to be fairly contagious. And, the closer together people are, the more likely contagion is. Which is not to say that we cannot do stuff to boost our immune systems, and cut down contagion, but we should be skeptical of claims this is enough.

At the moment the US CDC is estimating that in the 2018–2019 flu season there were 34,200 deaths from flu in the US . In 2017-18 there were 61,000 deaths, and in 2016-2017 there were 38,000 deaths

As of today, the current estimate of deaths in the US from COVID-19 is

98,004 and rising every day. There is little sign of a decline.

I admit these figures could be wrong, and COVID may turn out not to be as harmful as flu, but it seems unlikely at the moment…

Contagion rates and death rates do not have to be related. A disease can be highly contagious with an extremely low death rate, and it can have a high death rate but be mildly contagious.

Testing is difficult and often inaccurate with a new disease as well. So we would expect false positives and negatives, we do not know if these will cancel each other out.

The death rate certainly does not seem to be as high as originally expected.

However, some figures I’ve seen suggest that in many places people are dying at a far greater rate than last year, even after covid deaths are removed. Surprisingly this does not seem to be the case in Australia

There have been stories of significant undercounting of deaths, [2], [3], mistakes and of people being asked to revise figures downwards so as to get people back to work, and in the US until April 14 COVID-19 deaths had to be confirmed in a laboratory test while testing was not generally available, so where almost certainly undercounted.

We also now know that the doctors who were dying of heart attacks and strokes (which I was hearing about quite early on) were in fact dying of complications from corona virus, and were not counted.

There are now reports that children are getting rare inflammatory diseases, and that some people are remaining sick for a long time after infection [2]. So incapacity has to be counted as well as death rate.

At the moment some people seem to get the illness more than once. WHO has stated:

“There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from Covid-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,”

This is not unusual with diseases probably because they mutate, but there may be other reasons. I’ve seen reports suggesting Covid mutates quickly and mutates slowly, which suggest large degrees of uncertainty.

What looks like small death rates can mount up. If 60% of Australians get the disease, and the death rate is 1% that is still in the region of 156,000 dead people, and if we add incapacity to that disease consequences could well be significantly disruptive in many ways. If the disease continues for years, then of course it will likely mutate and the healthy people will get it as well. So the total death rate is unpredictable in the extreme.

We will probably never know, the true death rates in countries in which isolation is more or less impossible for ordinary people, India, Indonesia etc., as they won’t be able to test the bodies.

Getting vaguely accurate figures will take a while. But if we don’t act when we don’t have certainty we could kill a lot more people.

5) In Sweden, where there has been little done about the virus, conflicting reports are being given about the infection rate there.

Response: Yes, it could appear that information about Sweden has been politicised, because they may have gone for ‘herd immunity’. That means we should not just be skeptical about reports saying it has a high death rate, we should also be skeptical of reports that its doing well.

However I find the Murdoch Empire reports… 21 May that “Sweden is suffering the highest COVID-19 death rate in Europe”

“Nearly 4,000 people have died from the virus in Sweden, a figure many times higher per capita than those of its Nordic neighbours Denmark, Norway, and Finland, which all imposed strict lockdown measures.”

Stefan Lofven the Prime Minister, has faith their system will work in the long run, and there will not be a second wave of illness. The strategy is also relying on the Swedish sense of self-discipline, and not suprisingly the government can say “We get figures now that people are actually increasing their adherence to our advice [about distancing], not decreasing.”

We could be skeptical about his faith. He is making a prediction in a complex system… it is not guarranteed to be correct, and it is not cautious or conservative.

Other reports suggest that it was not working that well. “Just 7.3% of Stockholm’s inhabitants had developed Covid-19 antibodies by the end of April.” This is well below what seems to be required, to make a population relatively safe. Annika Linde who was the Swedish state epidemiologist from 2005 to 2013, has also expressed doubts as to whether the strategy is working.

Sweden is an experiment, which is useful as it gives information, but which because of what Sweden is like as a nation, may not be replicable elsewhere. I am skeptical of sigificant real confusion in the reported death rates.

6) Hospitals in the US are being paid more to diagnose patients as having the virus. I saw an article on this which had been “fact-checked” by a snopes-type crowd and they had to reluctantly admit it was true. This might be justified in that they may need more money if it is the case, but it also opens the system up to the inevitable over-diagnosing for the cash-strapped institutions to gain more resources in general. So who knows what the real numbers are?

Response: Payments to US hospitals are complicated matters. For example I read

“There isn’t a Medicare diagnostic code specifically for COVID-19.” The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that “the average Medicare payment [is] $13,297 for a less severe hospitalization and $40,218 for hospitalization in which a patient is treated with a ventilator for at least 96 hours.”

And

“A COVID patient on a ventilator will need more services and more complicated services, not just the ventilator,” said Joseph Antos, scholar in health care at the American Enterprise Institute. “It is reasonable that a patient who is on a ventilator would cost three times one who isn’t that sick.”

There also do appear to be special bonuses for COVID patients, which were instigated to protect US hospitals from loss of their normal business.

As suggested previously, there also seem to be pressures leading to undercounting – such as the initial dismissal of heart attacks and strokes, and people dying outside hospital or in old people’s homes, or people wanting other people to go to work.

As I have said previously, I am skeptical that we know the exact figures, and I am skeptical that there is any reason to think deaths are significantly overcounted as opposed to undercounted.

It is also probable that if hospitals are over-counting then insurance companies and government auditors will likely sort this out, at some cost to the hospital and its reputation.

7) I’m skeptical that what ‘they’ are doing is necessary. Some professional doctors are criticizing the the idea of wearing masks and social isolation.

Response: I’m skeptical of all doctors, including those who say isolation is pointless. However, wearing badly designed or useless masks badly is probably useless.

Isolation may not be necessary, but as remarked earlier we have less dead in Australia per head of population than in the US, where the regime is more uncertain. A lot depends on what you think human life is worth, under various circumstances, as with old people, poor people, black people etc. This is a value judgement. I’m skeptical we will have agreement on this issue.

Another problem we face is that medicine is an empirical science of complex systems. As a consequence, there will often be disagreement about best procedure and likely results.

Most medical pronouncements are based on deductions from theory. We cannot know if the pronouncements are correct until after the event. However, unlike neoliberalism, they will likely be modified by failure.

Physical isolation is generally thought to be the best way of preventing transmission. Ideally if the disease dies in a person, or adapts to being harmless, without being transmitted to another person, then the problem is ended

8) What about Madagascar and WHO?

I’m skeptical of the relevance of this.

I read that WHO commends Madagascar’s fight against COVID. I also read that they are prepared to test a local herbal remedy.

I would be skeptical of assumptions such medicines work, before proper testing. If there is a remedy which works and is traditional, then wonderful, and even better if it becomes a source of income for the locals.

WHO did apparently say, in this context, that use of untested medicines: “can put people in danger, giving a false sense of security and distracting them from hand washing and physical distancing which are cardinal in COVID-19 prevention.”

Yes WHO are skeptical, but why not?

There only seems to be a problem if the supposed remedy is proven, and then outlawed, or we cannot make enough of it, or corporations won’t distribute it without the patent or something. And that has not happened, yet. It is freely being consumed by those who can get it.

9) I’m skeptical Bill Gates would be involved if there was nothing in it for him. It is highly suspect that all of a sudden he has started giving WHO advice. I’m skeptical he is a philanthropist of any kind. His organization is motivated solely for profit.

Response: I’m skeptical Bill Gates is particularly evil or incompetent. I’m skeptical he is more evil or incompetent than those politicians who disagree with him.

Anyone can give WHO advice, the question is whether they listen. The wealthier and more prone to be involved in global medical projects the person is and the more funding they can provide, the more likely such an organisation is to listen to them. I don’t know whether WHO has changed any policies based on what he has said, and I personally know very little about Bill Gates and his motives at the moment.

He does not seem to be an issue in this part of the world, except to people who think he is trying to mind control them through 5G.

It is one thing to be skeptical that 5G is absolutely healthy, but another to hold that it transmits viruses. If the latter is true, then we have had a major set of scientific breakthroughs which no one seems to know anything about… I’m skeptical enough of these propositions to wonder who is encouraging them and why?

Gates has been trying to support vaccination, and he likes orthodox medical science, that seems to be enough to make him suspicious to many. Especially to the active financial class.

It could be that wealthy people who don’t obey the party line and who might show another way is possible, get attacked, and lied about, by those who support the current order of power and wealth.

I’d also ask what’s in it for Trump and Boris Johnson, Alex Jones and all the other right wing media players, claiming there is little to no problem… they actually have a direct stake in the power game.

Bill Gates does not have to play power games anymore, but it does seem he has been worried about pandemics for a while, like many other people, and has warned against them. I’m skeptical that this is evidence he actively wants a pandemic.

10) If it is an emergency then where are all the requisitioned football stadiums being turned into temp hospitals? The whole “crisis” is being handled by the existing infrastructure.

Response: I’m skeptical health emergencies always overwhelm the existing infrastructure.

As far as I can tell hospital wards were stretched in the US, and Trump was boasting about the military erecting temporary wards, but I am pleased that minimal activity has saved the US from a true crisis.

I have read that hospitals in Northern Italy were overwhelmed, and doctors were discussing who should receive treatment and who should be left….

There were crises of body disposal, and it was clear that systems were overwhelmed. President Trump seemed troubled by this at one stage.

I would however add, that I am skeptical that the crisis is over, or has necessarily reached its peak.

Because the pandemic is an issue involving complexity, we may be able to say things like “without isolation, or without successful vaccination it is likely the disease will continue to spread,” but we don’t know how badly countries will be affected for some while, or even after the event. We do not know all the variables, or even the properties of the virus, as yet. So prediction is messy.

To only be skeptical that the disease is serious, is not real skepticism, it seems to be directed, possibly at continuing current life and fantasising ‘all is well’, when this may not be the case.